|

|

From

his office in the 1857-vintage Land Office Building, Land Commissioner

W.C. Walsh had been watching the construction of the new Capitol since

the first shovel of dirt was tossed on Feb. 1, 1882. Not only was

he witnessing the biggest construction job to that point in Texas

history, Walsh had an official reason to follow the building’s

progress – he sat on the Capitol Board, the state entity overseeing

the project.

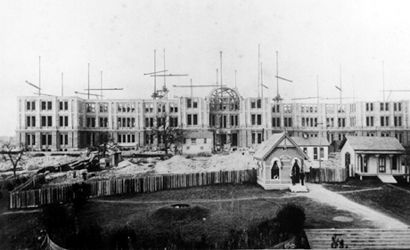

By the spring of 1887, the red granite, Greek cross-shaped base of

the future statehouse had been completed. Soon, work would begin on

the towering dome that would give the four-story government building

(the east-west wings are only three stories) its distinctive silhouette.

Born in Dayton, Ohio on the eve of the Texas Revolution in 1836, Walsh

had come to Texas with his family when

only four. They settled in Austin

when all it amounted to was an assortment of log cabins lining a broad

thoroughfare called Congress Avenue. Following his graduation from

Georgetown University in Washington, he returned to Texas

and went to work as a clerk in the land office. Walsh stayed there

until the beginning of the Civil War, when he signed up to fight for

the Confederacy. Though wounded three times, he survived the war.

Back in Austin, he farmed

and ran a rock quarry near Barton

Springs until 1873, when he became chief clerk of the House of

Representatives. Five years later, Governor R.B. Hubbard appointed

him to fill the unexpired term of Land Commissioner J.J. Gross. Elected

to a full term in November 1878, Walsh would serve until 1887.

As

the new Capitol

slowly took shape, as a member of the body charged with making all

the spot decisions that come up during such a large-scale project,

so did Walsh’s layman’s knowledge of architecture. Now, with construction

about to begin on the dome, Walsh grew increasingly uneasy. |

|

“The plans,”

Walsh later wrote, “called for a dome of brick, the lower thickness

of the walls to be five feet and diminishing gradually to the foot

of the lantern.”

He figured the weight of the brick, added the weight of the substructure,

and went to bed, not liking the number he got. Assuming he had made

a mistake, the next night he went over his calculations and got the

same result.

“The weight shown not only wiped out the ‘factor of safety’ but exceeded

the theoretical resistance of the foundation,” he wrote. In other

words, the base of the Capitol

would not support a brick dome. At some point, either during construction

or over the course of time, it likely would come crashing down and

possibly take much of the rest of the building with it.

Walsh tore up his calculations and burned the scraps. “As far as I

could, [I] dismissed the question from my mind for ten days,” he continued.

But then he ran the numbers again, coming to the same catastrophe-protending

figure. This time he submitted the numbers to someone else, who came

to the same conclusion.

“I then hunted up [Gus] Wilke, the building contractor, and broached

the subject,” Walsh wrote. “He told me the question had been worrying

him for months, and he wished I could get some action by the Board.”

Walsh did just that, but the timing was bad. All the state officials

who sat on the board, including Walsh, were leaving office. Only the

state treasurer would still be on the board.

“The general thought was that the outgoing Board had brought the building

through troubles and discouragement to its practical completion, and

it was now too late for the retiring board to take up the question—besides

the new Board ought to have something to worry over,” Walsh wrote.

Now a private citizen, Walsh remained concerned. When the new board

took no action on the dome issue after its second meeting, Walsh took

the matter to the new governor, Sul Ross. The governor asked Walsh

to submit his concerns in writing and shrewdly asked if he minded

the document being made public. The former land commission said he

had no problem with that, and soon his belief that the blueprints

for the new capitol contained a potentially disasterous design flaw

hit the state’s major newspapers.

When that happened, Ross appointed a panel of Texas

and Louisiana architects to prepare a report on the dome issue. “After

thorough study [the architects] reported to the Governor that my contention

was correct, that the existing plan was dangerous, and recommended

the substitution of steel plates for the brick, above the walls.”

|

|

Disaster likely

averted, Walsh was still not totally satisfied. He sent Capitol architect

Elijah E. Myers a copy of the report on the dome, asking for “at least

a personal explanation.” Myers’ secretary replied that his boss was

in ill health and unable to answer Walsh.

“The only theory I could ever work out was that the upper dome was

planned on the theory that the walls supporting it were treated in

the estimate as solid, while in fact from basement to top story they

were opened on four sides by immense arches. The mystery will never

be solved.”

By the time Walsh died on August 30, 1924, the ironclad Capitol dome

had stood for more than a quarter century and has now made it past

120 years.

© Mike

Cox - July

21, 2011 column

More "Texas

Tales"

See Texas

State Capitol Building |

The Capitol

Dome today

TE Photo, 2004 |

| Books

by Mike Cox - Order Here |

|

|