|

For

nearly a century, what remained of old

Fort Stockton stood mostly neglected near the now equally defunct

Comanche Springs, the once-robust West

Texas water hole that had drawn the Army in the first place.

Sure, in 1936 the state had put up an historical

marker at the site noting that the post had been established in

March 1859 by elements of the 1st and 8th Infantry and named for Mexican

War naval hero Commodore Robert Field Stockton, but only the most

history-minded folks paid the area any attention.

As time passed, however, civic leaders in Pecos

County began to understand the economic value of heritage tourism.

In 1981 the City of Fort

Stockton began a $1 million project to acquire a portion of the

960-acre tract originally leased to the military, restore the fort’s

remaining structures and reconstuct a couple of the barracks. |

The building

in the best condition when the project started was the old guardhouse,

a solid stone lockup built in 1868 not long after the Army reestablished

the fort following the Civil War. The lockup had quarters for the

guard on one side, a large holding cell on the other.

Though built to keep its occupants from escaping, the Army hoosegow

had not been designed for comfort. “The cells are not heated except

by the exhaled air of its occupants,” one officer observed, noting

that while the capacity of the jail should have been only two prisoners,

it often held as many as 15 men.

Officers stationed at the fort lived a little better in a series of

eight, one-story, adobe officer’s quarters lining one side of the

parade ground. They had 14-foot ceilings (back then builders considered

high ceilings healthful), and 24-inch-thick walls that kept the quarters

reasonably cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

Of those residences, only three remained by the time the city began

transforming the fort into a tourist destination. The city bought

Numbers 7 and 8 and restored them. Number 5 is still privately owned

but has been restored to be compatible with the other two quarters.

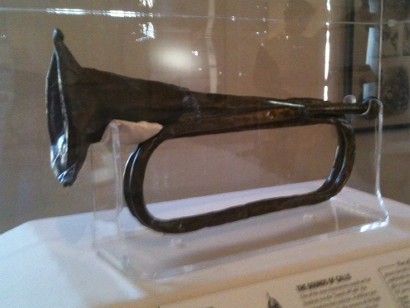

During

the restoration of No. 7, someone made a startling find: A battered

but still useable military bugle. The instrument was found stashed

beneath the flooring of the old residence.

No one could figure why someone would have placed the instrument there.

Adding to the mystery is that it was discovered in an officer’s residence.

Being a bugler was an enlisted man’s job. Usually each company had

two.

Maybe a sentimental soldier squirreled the old horn away for posterity,

realizing that with the vanquishment of hostile Indians in Texas,

the Army likely would never be returning to Comanche Springs. Perhaps

it was so banged up from hard use on the frontier that it was deemed

surplus and simply trashed, somehow ending up underneath the quarters.

Or possibly a soldier with a sense of humor swiped the instrument

and hid it in an officer’s residence as a practical joke.

However it got where it ended up, that bugle once played a central

role in the day-to-day life on the post. Every day, from the lone

medley of “Assembly of Trumpeters” (also known as “First Call”) blown

by an unlucky bugler whose duty it was to be awake as early as 4:45

a.m. on through “Taps” at the end of the day, the calls of that bugler

amounted to the garrison’s public address system.

Depending on the season, soldiers stationed at Texas’

frontier posts heard 25 or more different bugle calls at various times

of the day. In addition to those, soldiers occasionally experienced

a surge of adreneline when they heard “Boots and Saddles,” the lively

call that meant mounting up for action.

(To listen to the U.S. Army Band playing all the standard bugle calls

go to http://bands.army.mil/music/bugle/ )

By the time the Army abandoned Fort

Stockton fort on June 27, 1886, it had been more than five years

since beligerent Indians had posed any meaningful threat in West

Texas.

“The cavalry were mounted and the infantry riding in wagons and hacks

along the western portion of the trail, heading into the sunset with

a shroud of dust boiling up into the sky,” one person wrote of the

day the soldiers left. |

|

The old bugle

on display

Photo by Mike Cox |

In July 1986,

a century after the last of its soldiers marched away from the post

near Comanche Springs, the old bugle someone left behind was used

to play “To the Quarters” as folks gathered to mark the passage

of 100 years. Even after decades of disuse, the instrument still

sounded fine.

The bugle is now on display in a plexiglass case in the museum operated

by the Fort Stockton Historical Society in one of the restored barracks

at the old fort, its

story unknown.

© Mike

Cox - November

23, 2011 column

More "Texas

Tales"

|

| Books

by Mike Cox - Order Here |

|

|