|

It’s

not hard to figure that Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s time in Texas

was controversial and paradoxical. His entire military career was

that way, starting when he graduated last in his class at West Point

in 1861 until the bitter end at Little Big Horn in 1875. Custer stirred

controversy and debate in his own time, and historians have continued

the debate to the present day. Brilliant or buffoon? Martyr or imbecile?

The debate continues.

Distinguished by shoulder-length curly blonde hair, a red tie and

sailor’s blouse, he was something of a dandy and something of his

own creation. He became to the world the dashing and daring soldier

that he imagined himself to be when he was a boy growing up in Ohio.

That boyhood dream became a reality in the Civil War when Custer distinguished

himself as a daring – some said reckless – commander who led Union

troops successfully at Gettysburg and other major battles and pursued

Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Appomattox. |

|

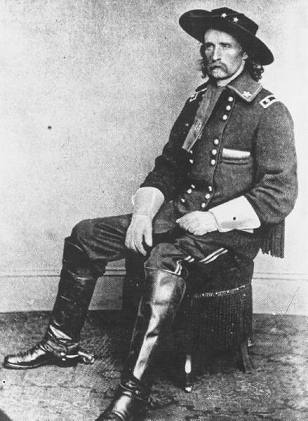

Gen. George Armstrong

Custer

Wikimedia Commons |

Lee’s surrender

at Appomattox ended the Civil War for most people, though Texas

was among the states that didn’t officially surrender until a month

later. The entire South, including Texas,

was ravaged by anarchy in the immediate aftermath of the war. The

U.S. also feared that the Confederates would regroup in Mexico under

emperor French emperor Maximillian.

Gen

Phil Sheridan sent Custer and a thousand or so volunteer troops to

Texas in 1866 to help restore and maintain

order, but Custer had his hands full maintaining order among his own

troops. The conflict arose over Custer’s refusal to let the soldiers

pillage and plunder the countryside to their heart’s content.

When they arrived at Hempstead

in August of 1866, Custer issued orders that made it clear that “foraging”

the land and its bounty would not be tolerated. Anyone found guilty

of disobeying those orders would have his head shaved and receive

25 lashes of the whip. Once bloody and shorn soldiers started showing

up in camp, the foraging stopped.

This measure, though successful, was also controversial. Custer was

accused of violating the Reconstruction Laws that “no cruel or unjust

punishment” be inflicted on “disturbers of the public peace and criminals.”

Custer argued that the punishment was neither cruel nor unjust and,

besides, it worked, which allowed him to follow his own orders in

regard to protecting Texas planters and

farmers from the troops.

The New York Times seemed to agree. “Gen’l Custer, knowing that the

trial for desertion was a farce, tried every humane way to save his

army from going to pieces, but failed,” a correspondent wrote. “He

then tried a new way, and flogged several men and shaved their heads.

This had the desired effect, but brought down the friends of these

soldiers upon him, who charge him with being disloyal, inhuman, and

everything that is bad. Now, I leave it to everyone if Custer didn’t

do right.”

Custer’s peculiar disciplinary measures alienated many of his troops

(and some authorities in Washington) but not the people who Texas,

who would generally recall Custer fondly, mainly because he had protected

them from those who would have preyed upon the land and the people

who lived on it and from it.

The ban on foraging was particularly galling to the soldiers as they

marched into Texas with a lot or orders

and drills but few rations. Custer assured them that rations would

be available at Hempstead,

but that turned out to be not true. The troops spent two unhappy months

there, and then marched to Austin.

The Custers moved into the old Blind Asylum building on the outskirts

of town, now restored and a part of the University of Texas campus. |

| For

Custer’s wife, Libbie, who wrote about her experiences in Texas

in her book “Tenting on the Plains,” the stay in Austin

was an idyllic time, coming as it did between the Civil War and the

Indian Wars on the Plains. They spent a lot of time horseback riding

and at the race track. Custer liked a little place on Shoal Creek

so much that he had a makeshift jail built there. “Armstrong was having

the time of his life, even while performing the unpleasant and unrewarding

task of taming Texas,” one biographer

wrote. For her part, Libbie enjoyed the luxuries of a bathtub, furniture,

a fireplace and a social life. |

|

It was nice while

it lasted. He was mustered out of the volunteers in February of 1867,

and would eventually take command of the Seventh Cavalry, where he

would meet his fate and seal his name in the history books at Little

Big Horn. The Texas legislature passed

a resolution of condolence, noting that Custer had endeared himself

to the people of Texas during his brief

stay.

© Clay Coppedge

"Letters from Central Texas"

February 23, 2011 Column

|

|

|