Books by

Michael Barr

Order Here: |

|

|

Government

gridlock and political polarization did not begin in the 21st Century.

In the 1880s, and for years after,

Blanco County was aflame in partisan politics and divided government.

Angry citizens were split right down the middle over the location

of the courthouse.

On February 12, 1858 the legislature in Austin

formed a new Texas county from parts of Comal,

Hays, Burnet

and Gillespie

Counties. The legislation stated that the new county would be called

Blanco, after

the Blanco

River, and that an election would be held to determine the exact

location of the county seat.

In those days, before fast travel and modern forms of communication,

government officials went to great lengths to insure that the seat

of county government was centrally located so all citizens had equal

access to it. State law directed that the county seat had to be

within 5 miles of the geographic center of the county unless two

thirds of the voters voted otherwise. The general rule was that

the county seat was not more than a day's ride from anywhere in

the county.

In the new county of Blanco,

residents selected a beautiful spot on the north bank of the Blanco

River as the site for the new county seat. They called the new

town Blanco.

The site was near the geographic center and met all the requirements

of state law.

In 1860 county officials erected a simple courthouse in Blanco.

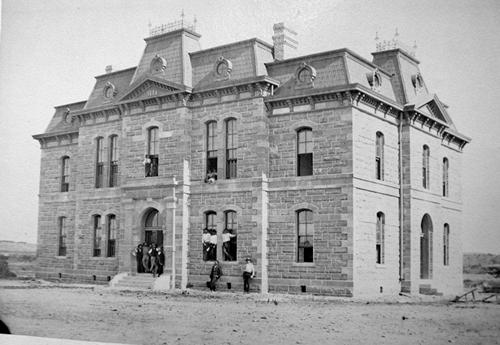

Then in 1885 voters approved the expenditure of $27,000 for a fancy

new limestone courthouse that still stands in the middle of the

public square.

|

|

|

But Blanco

County was unable to settle in to the rhythm of everyday life.

As new counties formed around it, Blanco

County was carved up and pieced back together again at the whim

of the legislature in Austin.

In 1862 Blanco County

lost a large area of land when the legislature formed Kendall

County, but legislators compensated Blanco

County by giving it parts of Hays

and Burnet Counties.

The problem was that once the county borders were permanently established,

the town of Blanco,

the county seat, was no longer near the geographic center.

Meanwhile,

the Johnson brothers, Andrew, Sam and Tom, established a cattle

ranching operation to the north of Blanco,

in the central part of the county. With a talent for political scheming

and backroom bargaining - a talent inherited by Sam's grandson,

the one who became president of the United States - the Johnsons

and their neighbors established a new town on the banks of the Pedernales

River, strategically located near the center of Blanco

County. From the beginning Johnson

City had one major goal: to wrestle the seat of government from

its neighbors, 14 miles to the south.

It took 12 years, some bloodshed and a lot of hard feelings to get

it done.

In January 1890 the citizens of Blanco

County went to the polls to decide, once and for all, the location

of their county seat. The election did not go smoothly. There were

rumors of ballot-stuffing. The San Antonio Daily Light reported

details of an election-day gunfight between a Blanco

supporter and a Johnson

City advocate. One man was killed and a deputy sheriff was shot

in the leg. Lawmen quickly whisked the shooter away to the jail

just ahead of the lynch mob. But in the end the citizens of Blanco

County voted, by a margin of 65 votes, to move the county seat

from Blanco

to Johnson

City.

After county officials moved out, the old Blanco

County Courthouse became, at one time or another, an office

building, a school, a hospital, a town hall, a museum, a theater,

a library and a restaurant. For a time the Blanco National Bank

used the vaults in the old building once used by county tax collectors.

The current Blanco

County Courthouse, in Johnson

City not in Blanco,

was built in 1916.

|

|

Sources:

Texas Local Government Code Chapter 73. Location of County Government.

"State News Condensed," San Antonio Daily Light, January 23, 1890.

"A Fatal Election Row in Blanco County," The Galveston Daily News,

January 23, 1890.

The Handbook of Texas, Blanco County. |

|

|