|

The

woman from Tennessee left no letters or diary to provide future generations

with any insight into her thinking, but it’s not hard to imagine her

feelings when she opened the envelope from Austin.

The communication came from Comptroller James B. Shaw. The state’s

chief financial official begged leave to inform her that under the

provisions of “An Act to provide for ascertaining the Debt of the

late Republic of Texas,” approved by the Legislature on Feb. 7, 1853,

her claim for the services rendered by her late husband had been audited

and authenticated. Enclosed she would find a warrant on the State

of Texas in payment of that service “in par funds, as having been

at that rate so available to the Government.”

That wording must have been about as easy for the 65-year-old widow

to understand as it is today, but Texas had finally reimbursed her

family for its loss. The widow’s name was Elizabeth Patton Crockett.

Her husband went by David. And he died hard.

It happened on the morning of March

6, 1836. Historians continue to debate whether the former U.S.

Congressman from Tennessee went down in the heat of battle swinging

his trusty rifle “Old Betsy” or faced summary execution after surrendering

to the Mexicans who had besieged the old mission for 13 days.

Eight weeks before, writing his children from San

Augustine on Jan. 9, 1836, Crockett had proclaimed Texas

“the garden spot of the world.” He said he intended to settle in the

northern part of Texas and “am in hopes

of making a fortune for myself and family bad as has been my prospects.”

Indeed, the celebrated frontiersman had never had much luck with money.

Nor had he fared a whole lot better in politics, having famously told

his former constituents, “Since you have chosen to elect a man with

a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to

Texas.”

Official proof of the return Crockett’s estate realized on his ultimate

investment can be found in the State Archives, where Second Class,

“B.” certificate No. 6127 remains on file. After Comptroller Shaw

signed the document on Dec. 2, 1854, his office sent Mrs. Crockett

a check from the grateful State of Texas for $24.

Though Crockett’s paycheck came 17 years late, on Dec. 23, 1837 the

Republic of Texas had issued Bounty Warrant No. 1295 to his heirs.

That certificate entitled Mrs. Crockett to 1,280 acres in North Texas

in return for her late husband’s government service, but the Comanches

who roamed the area saw the land as theirs.

Finally, eight years after Texas became

a state, Mrs. Crockett left Tennessee in 1853 with her two children

– a grown, married son named Robert Patton Crockett and a daughter,

Matilda, to claim her land. The Crocketts stayed in Waxahachie

until a surveyor could determine the boundaries of her land, a job

he undertook in exchange for half the property. What Elizabeth ended

up with was 640 acres on Rucker’s Creek, about six miles from present

Granbury. |

|

|

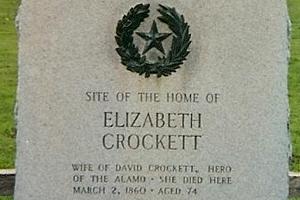

Site of the Home

of Elizabeth Crockett

Centennial Marker

Photo

courtesy Ruth Cade, 2008

See Texas Centennial |

Living in a log

cabin built by her son, Elizabeth spent the last six years of her

life in the place her husband had come to make his fortune. On the

morning of Jan. 31, 1860, wearing the widow’s black she had worn since

first learning of her husband’s death, Elizabeth left her cabin to

take a walk and shortly fell dead at the age of 72.

Elizabeth

was buried at the small community of Acton.

Four years later her daughter died and was buried near her.

In 1911, Senators O. S. Lattimore and Pierce Ward introduced legislation

appropriating $2,000 for “the erection of a monument over the remains

of Mrs. Elizabeth Crockett.” |

|

Explaining the

bill to his senate colleagues, Sen. Ward said he first learned of

the Crockett family’s Hood

County connection while a student at Granbury Methodist College

in the fall of 1880. By that time, of course, the only direct survivor

was Robert Crockett.

“Naturally I felt like making his acquaintance and I found him residing

near the banks of the Brazos River, manager and keeper of the toll

bridge that spans the river,” the senator said. “I would often visit

him.”

Ward recalled that Crockett took “great pleasure” entertaining “college

boys” and would “relate many incidents of his father’s career as he

had learned them when a boy.”

If Ward ever wrote down any of the stories he heard from Robert Crockett,

who died in 1889, they are not known today. But the senator’s bill

made it through the Legislature, and the monument was unveiled in

May 1913 by the widow Crockett’s namesake, her great-granddaughter.

|

|

Note the "Acton

State Historic Site" sign by the burial plot

Photo courtesy Sam

Fenstermacher, June 2005 |

Since 1949, the 12 by 21-foot burial plot at

Acton has

been a state park – Texas’ smallest.

The 28-foot marble monument features a statue of a bonneted

pioneer woman standing on a pedestal, her hand forever shading her

eyes as she looks to the west, eternally wondering when her husband

will come home.

© Mike Cox

"Texas Tales" - March

8, 2005 column |

Forum:

Subject: Crockett

Descendants

Elizabeth Gose Crockett (and we have photos) is my great, great grandmother...

more

- Melissa (Lisa) Jemison Roberts, August 14, 2007 |

Acton State

Historic Site Contact Information

c/o Cleburne State Park

5800 Park Rd 21

Cleburne

TX 76031

817/645-4215

http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us

Book Hotel Here > Granbury

Hotels |

|

|