|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

|

In

early spring of 1847, a remarkable treaty between German settlers

and Native Americans was negotiated on the banks of the San Saba

River in the hill

country north of Fredericksburg,

Texas. The unlikely parties to the long-standing agreement,

that was to eventually open up nearly four million acres for settlement,

were a former German baron and the representatives of the fierce

Penateka Comanche tribe.

Seeking to solve the problems of political unrest and overpopulation

facing mid-nineteenth century Germany by advocating immigration

to the Republic of Texas,

an organization of German noblemen known as the Society for the

Protection of German Immigrants purchased a large tract of land

in Texas. The land in question was part of the Fisher-Miller Land

Grant that stretched between the Llano and San Saba rivers. Unfortunately,

the Society purchased the land with little knowledge of the Texas

frontier and fell victim to a disreputable businessman, Henry Francis

Fisher. Fisher knew well that the land in question was inhabited

by far too many war-like Comanches to be suitable for settlement.

|

|

Enduring much

hardship on their journey from the Gulf

Coast, 439 German immigrants eventually made their way to central

Texas. However, the Society’s first attempt to populate the Fisher-Miller

Land Grant stalled at the settlement of New

Braunfels due in part to the financial mismanagement of Prince

Carl of Solms-Braunfels, the first commissioner general of the enterprise,

and the refusal of surveyors to enter a land grant infested by the

much feared Penateka Comanches. To make matters worse, 4000 new

immigrants were on the way to the new colony from Germany.

|

|

|

John

O. Meusebach

Wikimedia Commons |

|

The burden of

untangling this web of deceit and mismanagement fell on Prince Carl’s

successor, Baron Otfried Hans von Meusebach. Upon his arrival in

Galveston

in May 1845, Meusebach put aside his title of German nobility, adopted

the name John O. Meusebach, and rode to New

Braunfels. There Meusebach learned that in addition to the Society’s

wretched financial condition, and the Comanche problem, according

to the original contract with the Republic

of Texas, the Fisher-Miller Land Grant was subject to forfeit

if the land was not settled by August 1847.

In May 1846, Meusebach moved closer to satisfying the Society’s

obligation to settle the land grant by founding the community of

Fredericksburg.

However, in November the former baron received word of the 4000

new immigrants who were on their way from Germany. There was only

one possible solution to the problem of settling so many people.

Somehow Meusebach had to accomplish the seemingly impossible by

reaching an agreement with the Comanches to open the vast tract

of land to settlement that lay between the Llano and San Saba rivers.

On January 22, 1847, Meusebach rode out of Fredericksburg

with a company of forty men and three wagons and headed for the

heart of the Comancheria. Included in the company was interpreter

Lorenzo de Rojas who had been kidnapped by the Comanches as a child.

The expedition’s ultimate goal was to secure a treaty of peace with

the Comanches.

Soon after the expedition’s departure, Indian agent Robert S. Neighbors

arrived in Fredericksburg

with a message from Texas Governor

Pinckney Henderson, urging Meusebach not to venture into Comanche

territory for fear that the act would further arouse the already

hostile Indians. Accompanied by Dr. Ferdinand von Roemer, who had

been sent to Texas by the Berlin Academy

of Sciences to evaluate the mineral assets of the land grant, Neighbors

set off in pursuit of Meusebach’s party.

On February 5, Meusebach’s expedition was met by a party of Comanches

carrying a white flag, and after mutual assurances of their peaceful

intent, the parties shared a meal. The following day the Comanches

led Meusebach and his men to their main camp on the San Saba. The

entire camp rode out to greet the German settlers, everyone mounted

including the women and children.

At the urging of his interpreter, de Rojas, Meusebach ordered all

forty of his men to raise their rifles and discharge them into the

air, thereby disarming themselves as the huge party of Comanches

neared. Some of the men thought the act foolhardy, but it served

to build the Comanches’ trust, and in light of the overwhelming

numbers of warriors present, was most likely the only rational course

of action to follow.

Neighbors and Roemer arrived at the San Saba campsite on February

10, while Meusebach was waiting for the remainder of the Comanche

chiefs to assemble for the peace council. In his carefully written

accounts, Roemer noted Meusebach’s courage in walking among the

Comanches unarmed, a habit that earned the German the respect of

the Indians. They even honored him with the name El Sol Colorado

or the Red Sun, in part because of his flowing red beard. Among

the more prominent Comanche leaders who gathered at the assembly

were the political chief Old Owl, short and frail in stature, the

tall muscular war chief, Santa Anna, and the dour Buffalo Hump,

famed warrior and leader of the Great

Comanche Raid of 1840.

During the negotiations which began on March 1, and ended on the

following day, Meusebach’s lack of prejudice toward the Indians,

a view seldom shared by most whites, was reflected in his opening

words to the assembled chiefs. “I do not disdain my red brethren

because their skin is darker, and I do not think more of the white

people because their complexion is lighter.” Meusebach also stressed

that his people were neither Texan nor Mexican, two peoples the

Comanches hated the most. Even more important than his words, however,

were the terms of peace offered by the former German baron.

|

|

|

Unlike most

Indian treaties which were usually no more than articles of surrender,

heavily weighted in behalf of the whites, the treaty offered by Meusebach

provided for an equal balance of recognition and dignity as between

good friends and allies. First, the Comanches agreed to share their

hunting grounds with los Alemanes and grant the German settlers

and the Society’s surveyors free access to the land between the Llano

and the San Saba Rivers in exchange for $3000 in presents and supplies.

The Germans also granted the Comanches free access to their settlements

to “go wherever they please,” and finally, both sides agreed there

would be mutual reports of any wrong doing.

On March 3, the Germans loaded their wagons and began the return trip

to the settlements. The company was soon joined by a large band of

Comanches, including women and children, under the leadership of Santa

Anna. After crossing the Llano River on March 5, the Germans and Comanches

shared a camp near Enchanted

Rock the following evening, and reached Fredericksburg

the next afternoon. The company’s arrival happened to fall on a Sunday,

and Meusebach and his men were greeted by a festive crowd dressed

in their colorful best who, according to Roemer, “rejoiced when they

saw us return at the head of and in peaceful association with a troop

of Comanche Indians.”

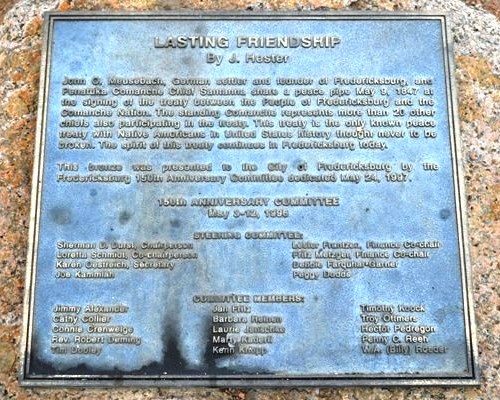

The Meusebach-Comanche Treaty opened up a vast stretch of land for

settlement that would one day become all or part of ten Texas counties;

a total of nearly four million acres. Other than the presence of Indian

Agent Robert Neighbors at the negotiations, the United States played

no part in the treaty except to later recognize it. The agreement

reached on the banks of the San Saba River remains the sole treaty

negotiated between a Plains Tribe and settlers as private parties,

and is believed to be the only pact between whites and Native Americans

that was never broken. The Meusebach-Comanche treaty was truly an

achievement of note by John O. Meusebach, a man of determination,

courage, and vision.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas Past"

August

1, 2012 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

References >

|

References

for "The Meusebach-Comanche Treaty"

|

|

Davis, Joe

Tom (1982), Legendary Texans, Eakin Press, Austin, TX, ISBN

0-89015-336-1.

Fehrenbach,

T.R. (1968), Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans,

Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, NY, ISBN 0-02-032-170-8.

Jefferson,

Morgenthaler (2007), The German Settlement of the Texas Hill

Country, Mockingbird Books, ISBN 978-1-932801-09-5.

King, Irene

Marschall (1987), John O. Meusebach, University of Texas

Press, Austin, TX, ISBN 978-0292740198.

Smith, Cornelia

Marschall; Tetzlaff, Otto W. "Meusebach, John O." Handbook

of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fme33),

accessed May 3, 2012, Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

|

|

|