|

A

New Yorker who grew up in Indiana, Gail Borden came

to Texas in 1829, five years after his

brother Thomas arrived as one of Stephen

F. Austin’s colonists.

Lacking much formal education, Gail learned by reading and doing.

He and his brother worked at first as surveyors, with Gail eventually

becoming the equivalent of a tax collector in the provisional government

of Texas.

Border knew metes and bounds, but nothing about the newspaper business.

Still, he realized Texas needed a voice.

Since the brief appearance of the Gaceta de Texas in 1813,

only nine newspapers had been published in Texas. Just one sheet,

The Texas Republican, enjoyed any significant circulation when

Borden decided to venture into publishing in 1835.

With a R. Hoe and Company medium hand press purchased in Cincinnati,

the Borden brothers and partner Joseph Baker printed their first issue

on October 10, 1835 at San

Felipe de Austin.

On page two of the eight-page inaugural issue, Borden explained: “We

shall...endeavor to make our paper what its title indicates, the organ

by which the most important news is communicated to the people, and

a faithful register of passing events.”

The Telegraph and Texas Register quickly became the best read

and most authoritative paper in Texas.

In just two months it claimed a circulation of 500.

The printing press, Borden opined in his November 7 issue, was among

“the greatest and most important inventions of man” if used to improve

and enlighten the world, but if employed otherwise “it is productive

of the greatest evil.”

Borden’s newspaper went on to play a critical part in the Texas revolution,

but true to his philosophy, Borden did not fan the flames. Instead,

he and his partners printed stuck to the facts as best they could.

“It has never been the object of this paper to forestall public opinion,

and to crowd upon the people our own views in a matter so important

as that touching a change of government,” Borden editorialized. |

|

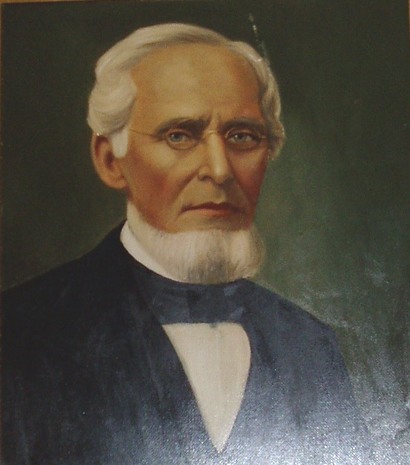

Oil

Portrait of Gail Borden

Photo of Portrait courtesy Karen Ross |

On February

20, 1836, the newspaper reported that General Antonio Lopez de Santa

Anna was on his way to Texas with thousands of troops. He had promised,

the Bordens wrote, “to leave nothing of us but the recollection that

we once existed.”

The newspaper served as a medium of communication for the revolutionary

government as well as preserving the history of the struggle. The

Bordens printed many public documents, including 1,000 copies of a

handbill containing the text of William

B. Travis’ last letter from the Alamo.

The letter itself has not survived, but enough copies of the handbill

made it through the revolution to save Travis’ words for posterity.

Borden learned on March 17 that the Alamo

had fallen. The Texas Republican having suspended publication,

the Telegraph was the first newspaper to report the grim news that

Santa Anna had overrun the old mission and killed every defender.

The provisional government and its citizens soon undertook a general

flight eastward, the Mexican Army not far behind.

The Bordens remained in San

Felipe for the time being, reporting more details of the Alamo

in their March 24 edition. Three days later, realizing they were the

only source of information left, they joined the flight. They got

help in crossing the Brazos with their press and type cases from the

Texas military. From the east side of the rain-swollen river, Borden

watched San

Felipe – and his print shop – go up in smoke as the Texas rear

guard torched the village.

The Bordens set up shop in Harrisburg, on Buffalo Bayou, and started

working on another issue. “We promise the public of our beloved country

that our press will never cease its operations til our silence shall

announce…that there is no more in Texas

a resting place for a free press nor for the government of their choice,”

Borden wrote in the April 14, 1836 issue.

Only six copies of the Telegraph had been printed before Mexican

soldiers burst into the office, seizing the press. Grabbing what they

had printed so far, the Bordens managed to escape by boat for Galveston,

where the government had gathered.

The Mexicans burned the town and sank the press and all the type in

Bray’s Bayou. A week later, Sam

Houston’s army defeated Santa Anna at San

Jacinto, but Borden had no press to tell the story.

In July, with a new press purchased on credit in New Orleans, the

Bordens relocated to the republic’s new capital, Columbia,

a small town on the west bank of the Brazos. With the first session

of Congress to convene there that fall, the first issue of the Telegraph

in its new location came out on August 2.

With new partners, Borden continued his association with the newspapers

until June 20, 1837 when he left Texas,

eventually to make another contribution to society – he invented canned

milk.

During a 20-month period, Borden had produced 74 editions, chronicling

some of the most important events in Texas history. Texas historian

Dr. Joe B. Frantz summed up the pioneer newspaper publisher’s philosophy

in 12 words: “He believed in a free press, but also in a free public.”

Author’s note:

Like Borden’s milk, this column is a condensation of an essay on the

Texas Telegraph and Register I wrote for “The News in Texas,” a book

published in 2005 by the University of Texas Press for the Center

for American History.

© Mike Cox

"Texas Tales" March

5 , 2009 column |

|

|