|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

| The

attempts of the Filibusters to

wrest Texas from the hands of the Spanish,

and later the Mexicans, were largely unsuccessful, however, their

efforts focused the attention of many Americans on a vast and empty

land that was ripe for settlement. One of the first men to take notice

was Moses Austin, an American-born Spanish citizen. Austin

had originally emigrated to New Madrid in Spanish Louisiana from Connecticut

to operate a lead mine and assist in the settlement of 30 families

from the United States. For twenty years, Austin prospered in Louisiana,

as the territory was first reacquired by France and then sold to the

United States in 1803. However, with the Panic of 1819, he was suddenly

faced with financial ruin and a burdensome debt. |

|

To the south

lay the Arkansas country, just beginning to open up to settlement,

but Austin was neither a homesteader nor a cotton planter. His forte

was business, and he felt sure that he could repeat his former success

of bringing settlers to New Spain by again following the Spanish

frontier; this time to Texas. After

discussing his decision to become a Texas land empresario with his

son, Stephen, Moses Austin set out on the 800 mile ride to

San Antonio de Bexar.

Upon entering the old Spanish town in the fall of 1820, Austin found

an atmosphere rife with ill feelings toward all Anglo-Americans.

General Arredondo, Spanish Commandant of the Eastern Provinces,

had recently crushed Dr. James Longís last attempt at filibuster,

and he gave Governor Martinez explicit orders that no Americans

were permitted to enter Texas on any

pretext. Under these circumstances it was not surprising that Governor

Martinez refused to speak with Austin about his plan when he learned

the man was an American. In spite of producing papers proving that

he had been a Spanish citizen for many years, Austin was ordered

to leave Bexar before sunset or he would be placed under arrest.

Moses Austin left the governorís palace, a near broken man, his

dreams shattered, but he was to find salvation in the form of an

old friend, Felipe Enrique Neri, the Baron de Bastrop. The

Baron had emigrated from Holland during the turmoil of the French

Revolution and founded the town of Mer Rouge in Louisiana. Later,

when France reacquired Louisiana, the Baron, preferring to remain

a Spanish citizen, moved to Texas and

founded the settlement of Bastrop.

The Baron de Bastrop was always welcome at the governorís palace,

and even General Arredondo liked him and appreciated his political

stance in behalf of the Royalists.

|

|

|

Baron

de Bastrop Monument

Wikipedia

|

|

Bastrop agreed

to serve as Austinís agent and help present his old friendís petition

requesting that Austin be granted authority to settle 300 families

in Texas. In support of the petition,

Bastrop advanced three arguments, in addition to his and Austinís

reliability as long-time citizens of New Spain. First, the danger

that the Comanches represented would never be addressed until central

Texas and the lands adjoining the Comancheria were settled, creating

a buffer between the Comanches and the Mexican settlements of south

Texas. Second, for three centuries few Spanish settlers came to

Texas, and in fact, many of those who

had come were returning to Mexico. Finally, American settlement,

if properly controlled, could succeed in Texas

as it had in Louisiana.

At a second meeting with the Governor, both Martinez and the ayuntamiento,

the governing council of Bexar, approved Austinís petition and forwarded

it to General Arredondo in Monterey. Convinced that Austinís colonists

might well serve as a barrier between the Comanches and the Spanish

settlements, and that American landowners with an interest to protect

could well help to prevent future filibusters, Arredondo also approved

the petition.

Confident of success, Moses had already departed for the east to

begin recruiting settlers for his new colony before the news of

Arredondoís approval arrived. Unfortunately, he became seriously

ill on the long journey home and was dying when he learned his efforts

at securing a land grant had succeeded. On his deathbed, Moses asked

his son, Stephen, to carry out his dream of establishing

a colony in Texas.

|

|

In the wake

of the ongoing financial panic, Stephen

Austinís prospects were not much better than his fatherís

had been, and he gladly put aside his plans to practice law and

headed for Texas. The first thing Stephen

did upon his arrival in San

Antonio in August of 1821, was to meet with Erasmo Seguin, a

well-known and respected citizen of Bexar, who had been appointed

by Governor Martinez to assist him. After a brief discussion on

the laws and customs of Spanish Texas, Seguin escorted Austin

to the governorís palace. There Martinez legally transferred Moses

Austinís empresario grant to his son.

Once the grant was officially transferred, Austin was free to choose

the site for his colony. He spent the next three weeks in the saddle

with Seguin, looking over the area south and east of San

Antonio and finally selecting a strip of land that ran between

the Lavaca and San Jacinto Rivers. As far as Austin was concerned,

the location was perfect. The land was not heavily forested and

difficult to clear like that of east

Texas, although there was adequate timber, and unlike west

Texas, it received more than enough rainfall to successfully

raise crops. In fact, the grassy prairie between the rivers was

a perfect place to grow corn,

sugar cane, cotton, and other

crops familiar to his future settlers.

Stephen Austinís

next step was to travel to New Orleans and begin recruiting colonists.

The success of his colony would rest in part on the settlers he

selected. By the terms of his empresarial grant, the colonists had

to be persons of good character who were either Catholic or would

agree to become Catholic. They also had to pledge their loyalty

to the king of Spain. Almost as important as meeting the terms of

the grant, all prospective settlers had to be willing to accept

hard times at first and be able to provide for themselves.

|

|

|

Austinís grant

allowed him to settle 300 families in Texas.

These original colonists would eventually become known as the

ďOld Three Hundred.Ē Settlers who claimed to be farmers would

receive one labor, or 177 acres of land, and those who professed

to raise cattle could obtain an additional sito, or square league

of 4,428 acres. Most colonists qualified for both. Beginning in

1821, colonists began to arrive by land through Nacogdoches

on the El

Camino Real, and by sea on Austinís small ship, the

Lively. The Baron de Bastrop, as the Spanish government's land agent,

issued titles to the settlers after Austin ensured they were fully

qualified.

During the first year of the colonyís existence, 1822-23, life was

difficult for both Austin and the settlers. Mexico had recently

gained itís independence from Spain, and Austin was forced to travel

to Mexico City to defend his empresarial grant. For a year, he pleaded

his case before a revolving door of Mexican governments before the

grant was once again approved. Meanwhile, in the colony, a severe

drought devastated the settlersí crops, and continual raids by the

Karankawa Indians practically brought new emigration to a standstill.

Some families gave up and returned to the United States.

When Austin returned from Mexico in the summer of 1823, the fortunes

of the colony quickly began to improve under his leadership. First,

he organized the militia and drove the Karankawas entirely out of

the colony. The ďranging companiesĒ Austin created were the forerunners

of the Texas Rangers. He then made treaties with the Witchitas and

Tonkawas which effectively ended further horse raids along the Brazos.

While in Mexico, Austin learned to speak Spanish and gained the

trust of Mexican officials. This enabled him to influence the passage

of laws beneficial to the colony like the laws freeing the colonists

from taxes, and granting them homestead rights, so their homes could

never be seized in payment for a debt.

|

|

|

With the assistance

of the Baron de Bastrop, Stephen

Austin founded his capital, San

Felipe de Austin on the west bank of the Brazos River at

the ferry crossing on the Old San Antonio Road. The Mexican governor

named the settlement to honor both the colonyís empresario and the

governorís patron saint. Though it remained the center of colonial

activity for many years, San Felipe never grew in relation to its

historical significance. The town was later destroyed by Santa Anna

during the Texas Revolution, and although it was eventually rebuilt,

never regained its importance.

Austin performed many different functions for his colony, including

acting as the settlersí representative to the Mexican government,

issuing land grants, translating Mexican laws into English, settling

minor disputes, and communicating the governmentís latest policies

to the settlers. As empresario, Austin had enormous powers; he was,

in fact, a dictator in all but name only, with the authority to

appoint any official he chose, and to establish all the rules and

regulations he thought necessary to maintain the smooth operation

of the colony.

Since the colony was excused from taxes, church tithes, and customs

duties, the Mexican government had little interest in it. As far

as they were concerned, it was created for the sole purpose of acting

as a buffer between their settlements along the Rio Grande and the

Comancheria. Austin was also commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in

the Mexican army and served as the military and political commander

of the colony. He was even permitted to develop and codify his own

laws; an awesome power that he seldom exercised and never abused.

|

|

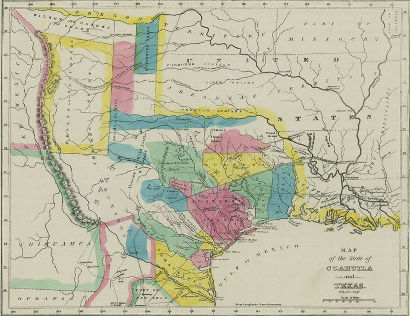

Map of Mexican

province of Coahuila and Texas in 1833 showing several land grants.

click

on map for large image. Wikimedia Commons |

| Stephen

F. Austin was far from the only empresario in Texas history. In

1825, the colonization law of the state of Coahuila y Tejas provided

for other individuals to apply for land grants, and by 1830, about

30 men had done so. Even Austin applied for, and was granted, additional

land. The second most important empresario, Green DeWitt, received

his grant in 1825. He founded a colony southwest of Austinís original

grant with headquarters at the settlement of Gonzales.

De Witt was granted authority to settle 400 families. |

|

|

A native of

Mexico, Martin de Leon, was another important empresario.

De Leon settled 200 families near the Gulf Coast between the Lavaca

and Guadalupe Rivers and founded the settlement of Victoria.

Arthur Wavell and Ben

Milam received grants in Northeastern Texas. Haden Edwards

also received a large grant near Nacogdoches,

but he lost the land after leading the Fredonian Rebellion. Europeans

like James Hewetson and James McGloin, natives of

Ireland, established colonies along the Nueces River.

Thanks to Stephen

F. Austin, ďthe Father of Texas,Ē and other dedicated empresarios,

the population of Texas stood at nearly 20,000 citizens by early

1830, most of them from the United States. In addition, many small

communities emerged in east and south Texas, and San

Felipe, Gonzales,

and Victoria

were now thriving towns. The old settlements of Nacogdoches,

La

Bahia, and San Antonio

had grown considerably. However, before long, the thousands of new

Anglo-American settlers would weary of a Mexican governmental system

that offered very little in the way of personal liberty and basic

human rights, and the stormy winds of revolution would soon begin

to stir across the vast land known as Texas.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas Past"

October 1, 2011 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

|

|

|