|

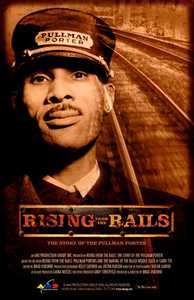

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

I

have always loved railroads, both the trains and tracks. I remember

when I visited my grandparents during summers when I was just a boy.

They lived in a small East

Texas town that really doesn't even exist anymore. But the Kansas

City Southern Railroad came through there on its east-west line. Going

east the train had to climb a long two-mile hill. It started blowing

its whistle long before it arrived in town. My grandfather would always

be out on his front porch waiting to see the train. I don't think

he could see that well at this point in his life, and the tracks were

actually about a quarter mile from his house. But he could definitely

hear the whistle. This was what was important to him. I'm sure the

train was just a blur, but the whistle let him know that a long train

was moving through the little hamlet. I always wondered if he had

any longings to wander left over from his early days. He would always

talk to me a little wistfully as he pointed out certain cars on the

train. From that point on I was hooked. One railroad line in particular

has been for me an umbilical cord that has connected me to my roots

and my life. I have lived close to this line for most of my life.

It always reminds me of where I've been and where I could have gone.

I grew up in a city in Louisiana. Our home was so close to the Southern

Pacific Railroad (SP) that every time a train passed by, the house

would shake just as though we were in an earthquake. Cracks would

develop in the ceiling, windows would rattle, and I was convinced

that the earth moved. When I was little the line still had steam engines,

and fortunately for me there was a passing track right behind the

house. Only our backyard and a highway stood between those trains

and me. Whenever a train pulled over on the siding to let another

one pass, I could examine the engine up close. Sometimes the engineer

would talk to me. The line was a busy one, so all day long I was seeing

trains, or at least hearing them. At night the mournful whistles woke

me up. I didn't mind. I loved the sound.

The SP was the only railroad I was familiar with in my younger days.

I got older and my parents trusted me to explore the territory surrounding

us. This is when I discovered the line that has meant so much to me.

This railroad started out as the Texas & Pacific (T&P). Over the years

the original T & P became the Missouri Pacific (MP) and now the Union

Pacific (UP). But the name is not so important as my connection to

the line.

The T & P had a rail yard within a couple of miles of my home. It

was very near the junior high school I attended. In fact, all day

long I could hear whistles blow and the sounds of switching as I sat

in my classrooms. After school, instead of going home, I headed for

the yards. There were several workshops on the edge of the yards.

Most of these had long been abandoned, but they were not stripped

of their insides. I found all kinds of rusty machinery, tools for

various usages, wheels, and even a detached smokestack from a steam

engine. Something I didn't want to find - rats - were all over the

place. My special treasure was an old passenger car. All the seats

were still in place and covered with so much dust that one could have

planted a garden within. But I would sit in the car, look at the switch

engines outside and imagine myself on a journey. My life's journey

has never been far removed from the T & P line. It has kept me attached

to a particular area of the world and to the many characters - a gaggle

of goofballs, really - I have met along its route. It offered both

hope for the places I could go and disappointment over missed opportunities

to travel in other directions.

The T&P was laid out in a, to me, rather unusual way. It has probably

been altered by now, but when I was a boy the basic east-west tracks

approached the city from the south and the main lines curved back

off to the southeast just before the rail yard began. A second line

for passenger service spurred off before the main line curve, went

through the switching yard, and terminated at a very stylish station

on the north end of downtown. Freight service on this spur was fairly

light, and passenger service was dwindling. |

I once had a

summer job for an auto parts firm whose location was near the old

T & P station. During the lunch hour I would explore the area around

the station. To my delight I discovered a second main line that ran

north through an alligator-infested swamp not far from downtown. The

line once ran up into Arkansas, but most of it had sadly been abandoned

by the time I came upon it; some small village in North Louisiana

was the new terminus. The T & P obviously used the line for storage

of boxcars, tankers, and hoppers. There must have been thousands of

them for me to mount and walk end to end on their tops. I was still

too young to know that the exploits with the railroad were prescient

in a way. I feel now that I've been on a train that has led nowhere.

No engine was there to pull it. But then all I knew was that I had

a fascination for these great mechanical beasts of burden that was

growing exponentially.

My desire for exploration was satisfied by another partially abandoned

branch of the T & P. This one forked off the main line south of the

city, about five miles before the great southeast curve. It once traveled

about seventy miles to a town in West Louisiana, but by the time I

was a teenager, the line ran only for a tenth of this distance from

its junction with the main line through a heavily wooded area. It

was used exclusively for storage. Again, I spent many hours walking

the tops of boxcars, pretending an engine was up front and that I

was a hobo riding the rails.

Eventually, the T & P station downtown closed and a new station was

built in the south part of town, just before the great curve. It was

little more than a glorified house trailer fixed up to look like a

train station. By this time the T & P had become the Missouri Pacific,

whose engines were bright blue and cabooses the traditional red. Passenger

service was almost at an end. When I was in college I managed to have

one more adventure on a MP passenger train.

I had a college friend who lived about 125 miles from my home. He

invited me to his house over the Christmas holidays, but I had no

way to get there except by bus or train. His hometown was on the MP

route, so naturally I chose the train. I went to the new station to

catch it and was amazed to see the sad state of passenger service

on the line. There my conveyance sat: a big blue engine and one rather

dilapidated coach - one coach! I knew the end of an era was in sight,

but I climbed aboard for what turned out to be my last ride on an

MP passenger train. The line paralleled both a state highway and the

Red River, and part of its route was through some swampy, marshy land.

The coach was almost deserted; the countryside appeared this way also.

Each served as a symbol for the other. Emptiness is neither a pretty

sight nor a pleasant feeling, and the trip made me sad to think that

a way of life that I grew up with was disappearing. The hands of Providence

removed me from the T & P / MP line after this trip, but I was destined

to come back to it someday. |

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

II

After

my graduation from high school, I chose to attend a college about

seventy-five miles to the east. The MP had no lines extending in this

direction, but I was pleasantly surprised to find that in my new college

town the Illinois Central (IC), an east-west line, crossed the Rock

Island (CRI&P), a north-south line, at a beautiful old train station

on the edge of downtown. The IC was still running passenger service

at this time, so it occupied the old station's waiting room and ticket

office. The Rock Island was strictly a freight line, which had an

interchange track with the IC. I spent time in which I probably should

have been studying to watch the IC stop to exchange cars with the

Rock Island. I was fascinated to watch the switch engines do their

work.

The IC ran right beside my first dorm room. It was easier to get downtown

to the movie theaters by just walking the tracks rather than city

streets. The railbed was in a deep gully, though, and the darkness

prompted me to walk faster. Once, on my way back to the dorm after

a midnight movie, a dog ran out of the ivy that covered the sides

of the gully and started toward me. This was bad enough, but when

I heard a voice say, "He won't hurt you," I almost lost it. Somebody

else was out on a late night trek in my domain. For a few weeks after

this I avoided the gully and took an alternate route to the theaters.

Two

events connected with the IC bring back both sad and funny memories.

Once a young deaf girl was walking the tracks to the downtown area

as a train approached her from the rear. The engineer obviously spotted

her and started blowing his whistle, but the poor girl couldn't hear

it. The engineer applied his brakes, but the train had built up too

much momentum to stop in time, and the girl was crushed beneath the

wheels. The whole town, including me, mourned for a long time. It

seemed such a senseless tragedy. The second event was humorous. There

was an underpass right outside the dorm in which I lived at the time.

The clearance for vehicles was around fifteen feet. I happened to

be looking out the window one day when an old truck carrying a high

stack - higher than the specified clearance - of crates containing

live chickens tried to go under the trestle. Chicken feathers and

dead birds were everywhere. From a distance it appeared to be snowing.

Clean up operations took a long time and the dead chickens were distributed

to the curious and the rubberneckers on the road.

I had no vehicle of my own at college and had to depend on the kindness

of friends to go home on weekends. I didn't go very often; I preferred

to stay at school and study. When I did get a ride home, I often couldn't

get the same ride, or any other one for that matter, back to school

on Sunday afternoons. Fortunately, the IC was still operating passenger

trains in the 1960s, and for $2.00 a ticket I could ride those seventy-five

miles to school. Once I remember arriving back in the wee hours of

the morning because of a detour the train was forced to take. A trestle

was out about twenty miles before my destination. The IC used the

North Louisiana and Gulf (NL&G) to travel forty-five miles to the

southeast where it could switch to the Tremont and Gulf (T&G) to go

back forty miles northeast to connect with its main line. Then it

had to backtrack thirty miles to the west to get to my college town.

It took hours to traverse this inverted triangle, but I loved every

minute of it. |

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

III

I

moved even farther east for graduate

school, to the Carolinas. My beloved MP was nowhere in this area.

But other lines that I could explore were present. The Southern Railroad

(SOU) was the main carrier though the college town. It skirted the

populated area, so I didn't pay much attention to it. A short line,

the Carolina and Northwest (C&NW), ran through the backwoods and foothills

of the Blue Ridge Mountains, crossing a major lake, connecting with

the Southern right before that line entered Georgia, and extending

another seven miles to the little mountain town of Walhalla, where

it came to a drop dead halt. This seven-mile extension was apparently

rarely used; I never saw any rolling stock on it. The C&NW scheduled

only one train a day, so I always made a special effort to see it.

Frequently, I was not very successful, but when it did appear it was

usually a short make-up, sometimes sans caboose.

During the Civil War, near Walhalla, the Confederates began construction

of a railroad through the Blue Ridge range. One granite giant required

a tunnel, and about a mile of it was actually hollowed out. Whether

the money ran out, or the war's end made the line unnecessary, I don't

know, but construction was stopped and the project abandoned. The

partial tunnel was afterwards used for the storage of cheese. By the

time I lived in the area tourists had discovered the site and would

walk into the tunnel to its end. I did this several times and let

my imagination run wild.

Another little town about forty miles northeast of the college was

the terminus point for a short line, the Pickens Railroad (PIC). It

was only eight miles long and connected with the Southern at Easley,

South Carolina. The line was curvy and traveled though some heavily

wooded land. What was really attractive about the Pickens was all

the railroad equipment stored at the terminus: old passenger cars,

several cabooses, some steam engines, and tons of boxcars. Apparently,

the whole reason for the line's existence was to serve a paper mill.

On a spring Sunday in the late 1960s my office mate, Amos T., and

I walked the entire line to Easley and back again. Both of us were

exhausted at the end, but we saw some scenery that most people would

die for: deep dark woods, flowing streams, wildflowers, and unfamiliar

bird sounds. We never encountered a train; they didn't run on Sunday.

|

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

IV

After

graduate school I moved back west, returning to Louisiana, where I

lived for about three years. My new hometown was 100 miles from the

place I had grown up. The MP line did come through the city, and seeing

those blue engines reminded me even more that my life swirls around

this tangible connection to my past.

But a new railroad caught my attention: the Arkansas and Louisiana

Missouri (A&LM). It was affectionately known as the "Gator Line" because

of the swampy terrain, full of reptilian creatures, that it traversed

for most of its route. An observer would get the impression that the

bed was one long trestle since so many of them were required to cross

the lowlands. Alligators and snakes would gather to sun themselves

around bridge pilings. If a train ever broke down along the way, repair

crews hesitated to go into the swamps to get it rolling again. The

tracks ran right in front of my apartment, so I frequently saw trains

on their way to Arkansas. I eventually had to say goodbye to this

picturesque line, though.

The move farther west to El

Paso placed me in an environment that required a major attitude

adjustment; in short, West

Texas was a cultural shock. A person from Louisiana and points

east would be accustomed to rain, green grass, trees, and noticeable

changes in the weather. West

Texas is barren, arid, and fairly meteorological stable. Much

of my time was spent attempting to overcome the negative thoughts

I had about the area and trying to regulate my life. My interest in

railroads waned somewhat.

The MP and Southern Pacific merged about 100 miles east of El

Paso and entered the city as a single line. The MP actually used

El Paso as

a western terminal point while the SP went on to California. Another

branch of the SP radiated out from El

Paso in a northeasterly direction toward the Texas

Panhandle and points in Kansas. This was the line I was most familiar

with because it paralleled the highway from El

Paso to Alamogordo, New Mexico. I traveled this road many times

either to the mountains or to White Sands National Park and was able

to observe long SP freight trains in and out of El

Paso. The Santa Fe (AT&SF) also entered El

Paso from Albuquerque and beyond. Trains tended to run on this

line at night, so I didn't get to see many of them. All the railroads

shared one station: Union

Station in downtown El

Paso. Out West I wasn't much of a steel rail explorer. I spent

too much time inside away from the heat and blowing wind. The MP heading

back toward Louisiana made me want to go home; the connection to my

past became more explicit. I often thought about hopping a freight

train and leaving, but marital obligations kept me fixed. |

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

V

The

obligations finally dissolved and I made my way back east but not

to Louisiana. Instead, I settled in the Dallas-Ft.

Worth area. By this time the Missouri Pacific had been absorbed

into the Union Pacific (UP) system. The engines were mostly a golden-yellow

with red lettering. Cabooses had been replaced by automatic signal

devices on the last car in line, thus eliminating the need for freight

train conductors. My first apartment was located about ten miles north

of the UP. Once an acquaintance of mine told me about a great steak

house I needed to check out, so one dark night I traveled the ten

miles south into unfamiliar territory and found the restaurant. It

was almost pitch black outside and I did not pay much attention to

my surroundings. I went inside, was seated and given water and utensils.

As I waited for my food, I noticed that my knife and fork were rattling,

the water in the glass was agitated, and the other patrons were looking

up from their prandial activities. Then I heard a rumbling noise and

the whole building started shaking. The movie Earthquake had been

released no more than a year previous to this time. I had seen it

in a theater which had been equipped with the special effects to make

the audience think that an earthquake was actually occurring even

as the movie was being shown. It was an impressive experience. My

first thought in the restaurant was: EARTHQUAKE! The truth was more

prosaic. The building was situated right next to the UP's main line

from California to New Orleans. A passing train caused the havoc in

my heart as I sat at my table. I obviously had not noticed the tracks

when I found the steak house. It's funny now, but I was genuinely

frightened at the time.

During the second installment of my singlehood, I managed to take

two train trips on AMTRAK. For the first one, the train left the Ft.

Worth station in the morning on a Friday and traveled down through

Texas to Laredo

on the banks of the Rio Grande across from Mexico.

This was in January, and I did not realize that the weather conditions

that far south could be so harsh. I took no warm clothing with me

and so was forced, due to financial constraints, to spend most of

my time in what would have been referred to during the Great Depression

years as a fleabag hotel. The place was a real dump, but at least

it was cheap and offered some shelter from the cold wind. AMTRAK ran

to Laredo

only every other day, so I could not come back until Sunday. Saturday

was a very long day. I did, however, enjoy the actual time I spent

on the train. The second journey was to Little Rock. The train left

Ft. Worth late in

the afternoon. It was almost dark by the time we were on the far side

of Dallas. The tracks paralleled

Interstate 20, and I noticed the train was out running all the cars

on the freeway. After that, darkness fell, and the rest of the trip

was blanked out, but the return one allowed me to see some nice scenery

in southern Arkansas and East

Texas.

A new marital situation allowed me to move closer to the UP, this

time about four miles south of the main line. I did not see many trains

everyday, but I could hear their whistles at night, a sound associated

with memories. I recalled all my years of never being too far away

from the railroad tracks. My life has been spent in a fairly concentrated

area. The T&P/MP/UP has run like a major artery through here. It has

appeared in both reality and in my dreams many times. My mind naturally

sees this phenomenon as symbolic. It points to my perpetual odyssey

over the land seeking something intangible; it is a reminder of possibilities

and lost opportunities, progress and regress, death and rebirth, an

escape route from the mundane, a chance to move to another place or

another job where success is more probable. The reach has always exceeded

the grasp. The UP is a silent witness to all my longings, a friend

that has shared my disappointments, my small triumphs and occasional

tragedies. The steel rail is a metaphorical umbilical cord that attaches

me to my beginnings.

When they were both in their eighties, my parents moved to the small

East Texas town of Gladewater,

also located on the UP California to New Orleans main line and in

a heavily wooded area of Texas. The scenery this route passes through

is almost indescribably beautiful: large pine trees, shocking violet

wisteria, and several rivers and streams. The tracks cut downtown

Gladewater in half.

When I was a kid, a movie theater stood on each side of the rails.

The one on the north side is long gone, but the southern one, the

old Cozy Theater, has become a local opry house. The place is popping

on Saturday nights, but whenever a freight train comes rolling down

the line - and they are quite frequent - the country music blaring

into the Texas night is drowned out by the roar of the engines. My

parents lived about five miles north of the UP, but little prevented

the sound of whistles floating through the night to reach my ears

whenever I visited them. |

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

VI

For

the last six years I have been teaching at a small junior college

about 100 miles west of Ft.

Worth. I don't drive this distance everyday, but instead rent

an efficiency apartment to stay in during the week. The UP main line

runs right in front of the campus. I must see twenty-five trains per

day on this route. I find myself looking out the windows instead of

concentrating on my classes. At night I can hear the trains, about

two miles north of my apartment, rumbling through town.

Anticipating all the daily trains provides some relief. From the campus

I can see switching activities and observe those golden engines carry

large loads up an incline. The college town has an old, stately train

station still standing, half of which serves as a place for equipment

storage for the railroad work crews. The other half is now a museum

containing many artifacts and historical documents from the time the

town was a mecca for the oil boom around the turn of the twentieth

century. Since I am somewhat a history buff, I have made more than

one excursion to this museum. By consulting old newspapers, local

histories, and railroad maps, I discovered that a second line once

ran through the town. For the first two years of my employment, one

of my hobbies, one that has provided me many hours of both distraction

and pleasure, was to trace any remains of the abandoned railroad.

The Wichita Falls and Southern (WF&S), incorporated in 1907, ran south

from Wichita

Falls, Texas, to Jimkurn,

where it met the Wichita

Falls, Ranger and Ft. Worth (WFR&FW), which extended from Dublin

north through Breckenridge

and to Jimkurn. In 1927

the WF&S assumed control of the other line and the entire system became

the 169-mile long WF&S. The major profit-making commodities that kept

the railroad going for forty-seven years were oil and grain products.

Passenger service, using standard travel cars, was offered into the

1940s, but over time patrons were confined to riding in modified cabooses.

Reports of this experience are not very flattering. Business had declined

on the WF&S by the early 1950s, and in 1954 the company was given

permission from the ICC to fold the line except for the part between

Graham, Texas, and Breckenridge.

This section was taken over by the Rock Island and finally abandoned

completely in 1969 when the CRI&P itself left the area. Of course,

when a railroad dissolves as a business the rails are removed and

usually sold for scrap; trestles are often dismantled, but the beds

are left intact. Over the years nature does its work, but some traces

of a former line always remain. Any persistent railroad aficionado

will always find hidden treasures if he puts his mind to it.

And I was determined. First of all, I found that two former stations

from the WF&S halcyon days are still standing, one at the terminal

point in Dublin,

the other in Breckenridge.

The former is used as an office building, the latter as an antique

shop. I started tracing the line from Wichita

Falls south. From Archer

City, locale of Larry McMurtry's The Last Picture Show, south

to Olney, the trackbed

of the WF&S is clearly visible in many places, but there are some

gaps where farmers have rendered the ground level for planting crops.

The line disappears between Olney

and Newcastle although

one can see where the trains passed through downtown Newcastle.

Next, is a train station that was jointly shared with the Rock Island

at Graham, a building

in sad repair, one that should be preserved, if for no other reason,

than for its architectural marvel. Farther down the road at South

Bend a magnificent concrete trestle still stands. The railroad

paralleled the Brazos River to Eliasville.

Several old bridge spans are in place even today. It is difficult

to trace the line from Eliasville

to Breckenridge

because it leaves the accessible highway and makes its journey through

mesquite trees and scrub brushes that dot this part of the world.

South of Breckenridge

the old line headed toward Ranger,

once a sprawling place full of oil derricks and wildcatters but now

a dilapidated shell of its former self. Signs of the location where

the WF&S crossed the UP main line can still be seen although the trackbed

is full of cacti and small plants. When Interstate 20 was built through

the area, much of the bed was plowed under, but if one looks closely

a little section of the old WF&S, paralleling a small creek, comes

into view. From this point south to where it connected with both the

Santa Fe and Texas Central (TCRR) in Dublin

almost all remnants of the line disappear except for the old station

at the end. Additionally, there is one place just south of Ranger

where a trainophile, if he looks closely, can notice the old trackbed

crossing a farm to market road: this, the terminal station, and nothing

more. |

The WF&S was

a witness to much of the history of west-central Texas. But nature

is reclaiming her own, and in another decade few signs of the old

line will remain. I spent the better part of four semesters trying

to follow the route, driving my vehicle on barely accessible roads

into tangled forests, sparsely inhabited farm land, and through hamlets

and small towns just for a glimpse of what was once, for a thriving

geographical area, a lifeline to the markets. This section of the

country is economically strapped now, and the old iron trail is gone,

but if it were a sentient creature, it would certainly be amazed to

learn that it gave an eager railroad buff hours of pleasure fifty

years after its demise.

Serendipitously, not far away from the school campus, another old

railroad once plied its way north from Cisco,

Texas, to Throckmorton.

The Cisco and Northeastern (C&NE) ran from a connection with the T&P

at Cisco in a northeasterly

direction to Breckenridge,

where it had a station and freight house across Gonzalez Creek from

the WF&S station. Then it curved in a northwestern path and went through

the village of Crystal Falls, the town of Woodson,

ending its trek at Throckmorton.

The length of the entire line was sixty-five miles, and it operated

successfully from 1918 to 1942. The rails were removed in 1943 to

be used to satisfy the steel demand during World War II. When I first

explored this part of Texas, I quickly found that the embankment for

the C&NE is clearly visible from Cisco

to about ten miles north. Many of the trestle supports were concrete

and these are still in place sixty years after abandonment. In Breckenridge

there are signs where the old station once stood, off Walker Street

on the eastern edge of downtown. The next evidence for the line's

existence are old stone pilings for a bridge span still standing in

the middle of the Brazos River just south of Crystal Falls. North

of this area is unexplored territory for me, a future project to look

forward to.

Another shortline once rolled through this area from 1918 to 1944:

the Eastland, Wichita Falls and Gulf Railroad (EWF&G). It branched

off the WF&S just southeast of Breckenridge

at a junction called Breckwalker, traveled south through Wayland and

Eastland, Texas, and

cut southwest to connect with the Missouri, Kansas and Texas (MK&T),

now the TCRR, at the now-deserted village of Mangum. The original

plans called for the tracks to extend from May,

Texas, to Newcastle, a distance of ninety-six miles, but only

twenty-eight miles were ever completed. The railbed is still visible

just north of Wayland and around Ringling Lake in Eastland.

In fact, at the latter location the locomotives once stopped to take

water from the lake. The line paralleled the Leon River south of Eastland,

and an acute observer will notice where it crossed Main Street on

the west side of the river highway bridge. The embankment is also

visible where the line crossed Highway 6 south of Eastland.

And then there is the ghost town of Thurber,

once a thriving mining locale with a population around 10,000, located

on a six-mile spur of the T&P that connected with the main line at

Mingus, Texas. Thurber

was the principal coalmining town in Texas from 1886 to the early

1930s. It supported stores, saloons, schools, churches, a large hotel

and an opera house. A brick factory was also established in the area,

one that supplied so many bricks that many towns circling Thurber

were able to pave city streets with them. Today, remains of the spur

rail line are quite visible as one passes through Thurber

on Interstate 20. The freeway actually cuts one branch in two, and

an observer can see how overpass trestles were constructed using brick

supports. Another branch of the spur veers off to the west and parallels

the interstate for several miles before abruptly ending at what was

probably a slush dump. Some restoration projects are in the works

at Thurber;

one can only hope the spur line will be on the receiving end.

|

|

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

| Photo

by Justin Parson, courtesy of AMS Production Group |

VII

I

like railroads. I like tracks. I like trains. I like watching trains.

I think I've made this profusely clear. Emily Dickinson can speak

for me in this regard: |

I like to see

it lap the Miles -

And lick the Valleys up -

Complaining all the while

In horrid - hooting stanza -

Then - prompter than a Star

Stop - docile and omnipotent

At its own stable door |

In particular

my beloved T7P/MP/UP has shared itself with me in an almost symbiotic

relationship. It is the steel artery of my life. I will probably always

live near it. Trains partially fulfill a predilection in me for wanderlust

and nostalgia. The cacophony of sounds, the sight of the rails, just

the movement of these mammoths take me back to the past, remind me

that I have wasted opportunity after opportunity, failed to go through

open doors, shut other doors intentionally, and burned a few bridges

along the way. In short, I have been a flaneur. For my approaching

dotage Melancholy has started adoption procedures to nurture me in

my remaining years. Trains remind me that I have not paid much attention

to forward progress. I want to apologize for this. I feel remorse

for mistakes I've made, wrong turns I've taken, and attitudes that

I've inculcated in myself and in others. To whom do I owe this apology?

God? My wife? Myself? To whomever: I'm truly sorry. And, I need trains

to enforce my regrets, to be constant reminders for me to strive for

improvement, to never stand still.

Trains, with their haunting sounds, will continue to move. This is

good. From my classroom window I see one approaching now. Think I

will dismiss the little cherubs and go take a closer look. |

|

|