|

Remembering

Sabine Pass

by Stan Weeber,

Ph.D. |

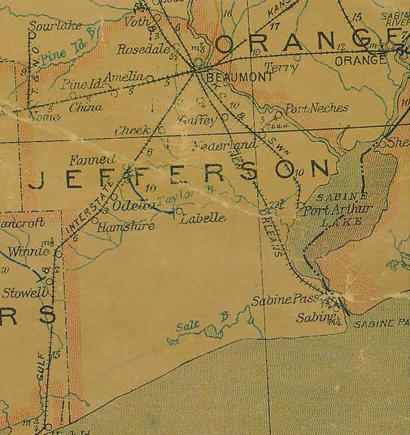

Even

if people forget that Hurricane Rita made landfall near Sabine

Pass, Texas in September of 2005 – and they probably will – history

still provides much to remember about this small town that is the

southeastern most place in the state of Texas.

Historical markers in the town note that the first settlers in the

area arrived in 1832. The next year, Sam

Houston assisted Nachogdoches politician Manuel de los Santos

Coy in acquiring a land grant. On January 19, 1839, General Houston

signed the charter that established the city

of Sabine. Houston was active in promoting the sale of 2,060 town

lots, and the city soon flourished, developing into a major port.

In 1860 the State Legislature approved a new charter for the city

and changed its name to Sabine

Pass.

The town was the scene of a memorable major Civil War engagement,

the Battle

of Sabine Pass, in September, 1863 with Confederate forces preventing

a Union attempt to capture the port and gain major inroads into Texas.

It was one of the most lopsided victories in naval history. Fewer

than 50 Confederate troops led by Lieutenant Richard

W. Dowling repulsed a fleet seeking to land up to 15,000 Federal

soldiers. Dowling’s company, mostly Irishmen from Galveston

and Houston, had been

comrades in arms since February 1861. Sabine

Pass was a strategic center for blockade-running whereby the Confederacy

exported cotton and obtained in exchange vital goods such as medicines

and arms. Here Dowling’s company built Fort Griffin, named in honor

of Lieutenant Colonel W. H. Griffin, the Confederate commander at

Sabine City.

The fort was earthwork strengthened with railroad iron and ship's

timbers, and amazingly it was unfinished when the Confederates learned

of the approach of 22 ships. Dowling kept watch, but ordered no response

to the early shelling by the Federals. When the first ships entered

range of Fort Griffin's guns, however, the battle began. Dowling himself

served as one of the gunners. The fort sent 137 shells toward the

targets.

Several books and research monographs have been written about what

transpired during the battle, each highlighting different aspects

although converging on certain themes. One is that the Irish Confederates

were skillful fighters, taking advantage of their knowledge of the

tricky terrain in Sabine Pass.

A second theme was the blundering of the Union troops, who needed

to station only one ship north of the fort to begin a broadside assault

that would have most likely ended in a Union victory.

The following basic facts of the battle are noted in the town’s historical

markers: Dowling and his troops held off the Union gunboats advancing

up the pass. The U.S.S. Clifton and the U.S.S. Arizona ran aground

early in the battle. The Clifton and the U.S.S. Sachem both surrendered

when disabled by cannon fire. After the battle, more than 300 Federal

troops became prisoners of war. Others were killed or missing; many

of those had been aboard the Sachem when its boiler exploded as a

result of a direct hit on the ship.

After

the war the town grew as the Federal Harbor Act of 1882 led to construction

of jetties and the development of inland ports along the Neches and

Sabine rivers. In October 1886, Sabine

Pass was the second largest town in Jefferson

County, boasting a new rail line and an optimistic outlook on

continued growth as a major coastal port.

On the afternoon of October 12 that year, just two months after a

hurricane had destroyed the Texas port of Indianola,

a fierce storm ravaged the town of Sabine

Pass. The hurricane's 100 mile-per-hour winds and the swiftly

rising water swept homes off their foundations and carried people

and animals as far as 25 miles away. Eighty-six people, including

entire families, were killed, and only two of 77 houses remained intact

after the waters subsided. Stories of survival have been documented

by historians, signifying the determination of residents to endure

the storm. Rescue and cleanup efforts began promptly, with the citizens

of Beaumont, Orange,

Galveston and Houston

providing boats, rescue teams and financial assistance. Special legislative

action provided tax relief for the storm-ravaged area, exempting citizens

from payment of state and county taxes in 1886. As one of several

difficulties Sabine Pass faced

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the 1886 hurricane contributed

significantly to the town's decline in the years to come as railway

maintenance proved difficult.

The

strategic Sabine Pass emerged

once again as an important defense base during the Spanish-American

War. As tension mounted between the United States and Spain during

the late 1890s, U. S. Representative Samuel Bronson Cooper of Texas

recommended the War Department begin plans for the defense of the

Pass. Major James B. Quinn of the Army Corps of Engineers in New Orleans

was authorized to direct construction of two forts on land granted

by Augustus F. Kountze. Work on the batteries was under way by May

1898, one month after the formal war declaration. Military efforts

were coordinated with area residents by government engineer J. L.

Brownlee. Although the emplacements were soon completed, the shore

guns were never part of military action at the Pass.

The natural topography of Sabine

Pass became one of the primary points of defense along the Gulf

Coast during World

War II. In 1941, the U.S. Navy established a Harbor Entrance Control

Post (HECP) at the Pass to provide defenses against potential enemy

activity in the area. Soon after, the U.S. Army installed artillery

emplacements at Texas Point, about 3 and one half miles to the south,

that included two 155mm Howitzer guns on Panama mounts, as well as

four munitions magazines at this site. The Army's lease of land at

Sabine Pass resulted in the location of a temporary harbor defense

unit manned by the 256th Coastal Artillery Regiment at Texas Point.

Other elements of the defense system included two base end stations,

an observation tower, signal stations, large coastal searchlights,

a battery commander post and part of the Coast Guard lifeboat station.

The munitions magazines also held other ordnance for area installations.

Working together, the HECP and the Army post utilized these storage

magazines to service the war effort.

Sabine

Pass has suffered an unfortunate string of experiences with hurricanes

that made landfall in or nearby the town. In addition to the hurricane

of 1866 that greatly affected the town’s growth as a rail center,

storms blew through in 1900, 1915, 1957, and 2005. Audrey, which hit

nearby Cameron, Louisiana in 1957, was the final straw in breaking

Sabine Pass’ quest for economic

development. As a result of Audrey, development moved north to the

cities of Beaumont, Port

Arthur, and Orange, which still

dominate the area’s economy today.

Sabine Pass’ colorful history

continued in 1959 when a native son and musician, J.P.

“Big Bopper” Richardson died in an Iowa plane crash which became

the story line for Don McLean’s 1971 classic song, American Pie.

The

last of the hurricanes to hit was Hurricane Rita in 2005. Rita appeared

early on to be a Category 5 monster that could totally and perhaps

permanently erase the city of Sabine

Pass. Fortunately for the people of the town, the hurricane weakened

to Category 3 before hitting them head on. Still, ninety percent of

the buildings in the town experienced some kind of damage.

My own field trip to this remarkable place was in early June, 2006,

over seven months after Rita struck. I was interested in finding out

if this history-rich place would be able to rise yet again from the

ravages of a horrific and devastating storm.

Entering

from the north on Texas 87, the scene was grim. Businesses on both

sides of the road were completely destroyed and appeared to me as

if the storm had just passed.

At the center of town at the intersection of highways 87 and 3322,

there were signs of life. Someone had purchased a soft drink machine

and placed it on his porch, and the place appeared to be an impromptu

community center after the storm. A restaurant nearby had reopened.

Across the street, the softball field was repaired and a crowd gathered

to see a game. Further west on 87, repairs to gravesites were underway

at the Confederate cemetery. Further down the road on 87, some new

dwellings stood out among the others that were in various stages of

repair. Sea Rim State Park was closed, a reminder of the ferocity

of Rita’s winds. At the McFaddin National Wildlife Refuge,

the occasional remnants of boats that washed ashore were the only

remaining signs of the hurricane.

Turning around and heading east back into town, I returned to the

major intersection. Heading right on to 3322, I went south to the

historical park near Fort Griffin. The park was closed but that did

not stop me from jumping over the orange fences, taking in the scene,

and imagining how the Battle

of Sabine Pass might have played out in real time. Much of the

information about the town and the battle that was shared earlier

was obtained from historical markers within the park. It appeared

to me that the Pass was now wider and deeper than it had been in 1863,

judging from the drawings in the historical monographs that I consulted.

This means that the Battle, had it been fought today, might have had

a much different outcome.

Going north back into town, I turned right at the main intersection

on to Broadway. Ahead was the most impressive part of the Sabine

Pass skyline, the offshore oil rig that was being built in the

waters of the Pass just east of town. On the way out to look at it,

the neighborhood looked much like the one on 87 headed west toward

Galveston: some

buildings totally repaired, others in various states of repair.

I am completely confident that the town of Sabine

Pass will come back. It is a resilient place, having come back

from four previous hurricanes. Rita is just another storm for the

hearty souls here to conquer. There is much here worth remembering,

not just about Rita but about the area’s rich past. I can only hope

that future historians will tell fewer stories of conflicts with people

and with nature, and more about the remarkable spirit of resiliency

and triumph in this tiny place, and how it thrived despite the long

odds against it.

© Stan Weeber

Associate Professor, Sociology

McNeese State U. |

|

|

|