|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

During

the unrest and confusion of pre-Revolution Texas and the establishment

of a new and independent republic,

the capital of the Republic of Texas shifted locations several times,

from San

Felipe de Austin, the capital of Stephen F. Austin’s original

colony, to the present-day capital city of Austin,

a town created for the sole purpose of serving as the Republic’s seat

of government. In between these historic sites, Washington-on-the-Brazos,

Harrisburg, Galveston

Island, Velasco,

Columbia

and Houston all held the

distinction of the being the Republic’s lead city, if only for a brief

moment.

San

Felipe de Austin was founded in 1824, near the site of John McFarland’s

ferry where the Atascosito Road connecting San

Antonio and Louisiana crossed the Brazos River. By 1835, San

Felipe had become the second largest town in colonial Texas with

a population of around 600. Stores offering merchandise imported from

the United States and inns and taverns providing lodging and meals

offered travelers their only respite across a wide wilderness that

stretched from Nacogdoches

to San Antonio. In

1829, one of the colony’s first newspapers, the Texas Gazette,

began publication in San

Felipe. The newspaper published the first book ever printed in

Texas. |

|

|

San

Felipe was also the center of political activity during the

events leading to the Revolution. The “People of Texas” met in session

there three times to protest Mexican policies and eventually consider

breaking free of Mexico; first at the Conventions of 1832 and 1833

and finally at the Consultation of 1835. San

Felipe also played a key military role in the Revolution. After

the disaster at the Alamo,

Santa Anna ordered his armies to converge on San

Felipe. The Texas army commanded by Sam

Houston retreated from Gonzales

to San

Felipe as the Texas settlers fled east in what became known

as the “Runaway

Scrape.” On March 29, 1836, Houston

ordered San

Felipe put to the torch to deny Santa Anna’s army a source of

supply. McFarland’s ferry was also destroyed. Unable to cross the

Brazos River, Santa Anna was forced to turn southeast toward the

fate that awaited him at San

Jacinto.

Many of San

Felipe’s colonial residents failed to return to the area after

the Revolution, and the town never regained the prominence it had

once held prior to its destruction. With the formation of Austin

County and San

Felipe’s designation as the county seat, the town at least remained

a center of local government for a time. However, the Texas government

did not return, and within a decade the county seat was moved to

Bellville. San

Felipe remained a small rural community well into the Twentieth

Century, taking more than 150 years to regain the population it

had held prior to the Revolution.

On March 1, 1836, the scene of the capital shifted once again to

Washington-on-the-Brazos.

There the Convention of 1836 met and adopted the Texas Declaration

of Independence on March 2. The delegates also wrote a Constitution

and selected an ad interim government headed by President David

G. Burnett. The Convention adjourned on March 17 when a report reached

town that Mexican cavalry had occupied Bastrop

only 60 miles distant. The news created panic. In the words of one

distraught delegate, the Texans were “hourly exposed to attack and

capture, and perhaps death.” The newly created provisional government

soon packed up and fled 70 miles eastward to the new site of Harrisburg

located on Buffalo Bayou.

|

|

For the next

three weeks the Mexicans continued in hot pursuit and the capital

of the Republic was anywhere that President Burnet happened to hang

his hat. On April 14, Santa Anna reached Harrisburg only to find that

Burnet and his government had escaped the previous morning on the

steamer Cayuga. The steamer headed down Buffalo Bayou to the

San Jacinto River and the town of New Washington on Galveston Bay.

The water route to New Washington followed many twists and turns,

but the town was only twenty miles distant by land, so Santa Anna

immediately dispatched a troop of dragoons in hopes of capturing Burnet.

The Dragoons arrived in time to see the President and his fledgling

government escape by rowboat to a schooner that would take them to

Galveston Island the next stop on the capital carousel.

President Burnet soon moved the capital to Velasco

where he negotiated with General Santa Anna who had been captured

by Sam Houston

at the Battle of San Jacinto.

The negotiations produced two treaties, one public and one secret.

The capital remained in Velasco

until October when Burnet declared the small Brazoria

County town of Columbia

the capital city. The newly elected Texas legislature met there for

the first time on October 3, 1836, however many Texans complained

that Columbia

was too small and isolated to serve as the capital. They demanded

a new location, and John and Augustus Allen provided an answer to

the dilemma.

The Allen brothers arrived in Texas from

New York in 1832. John was young, bright and fresh and soon became

an influential Texas senator. The dour Augustus was a bookkeeper who

provided the partnership with financial expertise. In 1836, the brothers

acquired a tract of land on Buffalo Bayou not far from the former

town of Harrisburg which had been burned in the Revolution. They named

the site in honor Sam

Houston in hopes of gaining his support in the search for a new

capital. The Allen brothers promoted their town by declaring “Houston

is located to command the trade of the largest and richest portion

of Texas.” As an incentive, the Allen’s offered to build a new capital

building to house the government at their expense. The offer was too

good for Congress to turn down. |

|

|

John Kirby Allen

Wikimedia Commons |

The capital building

was still unfinished in April 1837 when the government moved from

Columbia

to Houston, but Congress

convened without further delay. Lured by the promise of government

business, merchants and craftsmen began to flock to the site of the

new capital. Log cabins and structures of all varieties began to spring

up everywhere on unplanned streets, but not near enough of them to

accommodate the flood of new settlers. The Houston Telegraph reported

“This city is increasing with a rapidity unequaled by that of any

city in Texas…” Unfortunately, many of the newcomers were far from

desirable citizens. Stephen F. Austin’s cousin Mary Holley jokingly

wrote that the attraction of the riff-raff to Houston

may well be a blessing. It “concentrates the rascals, with the government

and its hangers-on, & leaves the rest of the people in peace.”

Unfortunately, the spread of disease was inevitable with so many people

crowded together in an area without adequate sanitary facilities.

People initially fell sick from drinking foul water straight from

the bayou, but that problem was solved when Congress invested $500

in the construction of cypress cisterns to collect fresh rainwater.

The city’s founder John Allen died in 1838 of what was most likely

yellow fever and 240 citizens perished in an epidemic the following

year. In spite of the problems, all was not darkness. There were also

encouraging signs of stability. The first school opened in 1839, quickly

followed by the first theater, a jail and a courthouse. Organizations

like the Chamber of Commerce and a local chapter of the Masonic Lodge

also sprang up. However, just as conditions were beginning to improve,

Congress began to speak of moving the capital again. |

|

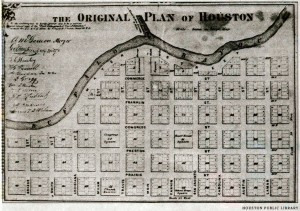

Map of early

Houston

Wikimedia Commons |

The speculation

that a new capital was in the offing was not without cause. Houston’s

marshy location on Buffalo Bayou, the nearly unbearable summer humidity,

the presence of yellow fever and other disease and the inadequate

accommodations were all ample reasons for complaint. Though many alternative

sites were discussed, one location in particular impressed Mirabeau

Lamar the Republic’s new president. He had first seen the site on

a bend in the Colorado River a few years before during a buffalo hunt.

Lamar not only admired the location for its scenic beauty, but also

for its healthy climate. He recommended the site to a five-man commission

appointed for the purpose of selecting a new capital, and after an

appraisal, the commission approved his recommendation.

The opponents of the new site complained that it lay too far to the

northwest in the “middle of nowhere.” In addition, they protested

that the location bordered on the Comancheria and would require constant

defense from the dreaded Comanches. The protests were also joined

by the citizens of Houston,

who were worried that their city would wither on the vine if it lost

the prestige of being the capital. However in spite of the protests,

Congress voted to approve the new location and named it Austin

in honor of the “Father of his Country,” Stephen

F. Austin. The government then demonstrated that it had learned

a lesson from the mistakes made at Houston

by appointing Edwin Waller to take charge of developing the new capital. |

|

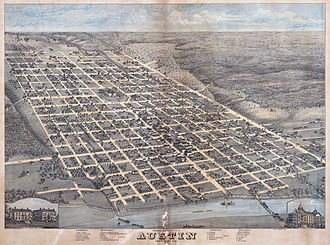

An 1873 illustration

of Edwin Waller's layout of Austin

Wikimedia Commons |

|

Waller, a signature

of the Declaration of Independence, was born in Spotsylvania County,

Virginia on November 4, 1800. He represented Columbia

at the Consultation of 1835 and served as a delegate from Brazoria

to the Convention of 1836. As a member of the convention, he served

on the committee that framed the Republic’s Constitution. Determined

to develop a town the Republic would be proud to call its capital,

Waller proceeded with honesty, foresight and meticulous care. Under

his supervision, a team of surveyors led by L. J. Pilie and Charles

Schoolfield carefully laid out a town on the north bank of the Colorado

River that was divided by a broad central boulevard named Congress

Avenue and bordered by Waller Creek on the east and Shoal Creek

on the west. The thoughtful design would allow Austin

to expand gracefully, unlike the helter-skelter sprawl that had

hampered Houston. Waller

also sold 306 choice building lots at auction for the benefit of

the Republic of Texas instead of some greedy speculator.

Construction on the capital began in May1839. The first thing Waller

did was build an eight foot stockade to surround the one-story frame

capitol building set back from Congress Avenue on a hill at what

is now the corner of Colorado and Eighth streets. Comanches were

known to roam the streets at night and every now and then a careless

citizen would lose their hair. A local politician reported that

“You were pretty sure to find a congressman in his boarding house

after sundown.” The site had been incorporated in1839 under the

name of Waterloo, but shortly thereafter the name was officially

changed to Austin. By

1840, the capital was beginning to spread outward from Congress

Avenue and the 856 residents of the city elected Edwin Waller to

the office of mayor for the valuable services he had rendered.

Unfortunately,

the city of Austin had

a very influential enemy, Sam

Houston. Houston

often described the new capital as “the most unfortunate site on

earth for a seat of government.” When he was reelected to the presidency

in 1841, he refused to move into the official residence, preferring

instead to take a room at a boarding house run by Mrs. Angelina

Eberly. Then in February 1842, Houston

saw his chance to return the capital to his namesake. A Mexican

force of 1000 troops under the command of General Raphael Vasquez

invaded Texas and occupied San

Antonio. Fear quickly spread that the troops would soon move

on the capital, and the President, arguing that the city was defenseless

against attack, ordered a special session of Congress to meet in

Houston. He also ordered

the secretary of state to remove the government archives to Houston.

Knowing that as long as the government archives remained in Austin

the city would be recognized as the official capital, the citizens

of Austin banded together,

formed a vigilante “Committee of Safety” and warned the government

officials who remained in the capital that any attempt to remove

the archives would be met with armed resistance. When his attempt

to revive Houston as

the capital failed, Sam

Houston compromised by ordering Congress to meet at Washington-on-the-Brazos

where the Declaration of Independence had been signed in 1836. After

the government was established, Houston

sent Captain William Pettus to collect the archives, but when Pettus

rode into Austin, the vigilantes lopped the mane and tail off his

horse and sent him back to Washington-on-the-Brazos

empty handed.

Frustrated, President Houston decided to dispatch Captain Thomas

Smith to make off with the archives under the cover of darkness.

Late in the evening of December 30, 1842, Mrs. Eberly, whose boarding

house business would suffer if the capital was moved, spotted Captain

Smith loading the archives into a wagon. She ran to the top of the

hill on Congress Avenue and touched off the cannon that stood in

front of the stockade surrounding the capitol building. The blast

aroused the town, and an armed posse of vigilantes ran Smith down

at Brushy Creek and retrieved the records. The vigilantes threatened

that anyone else who tried to steal the records would be shot.

The “Archives War” ended with Captain Smith’s failure, and Sam

Houston made no further attempts to move the records. For the

next several years, Austin

had more than its share of troubles with the population declining

to a modest 629. However in spite of the problems, a general election

held in 1850 voted overwhelmingly for Austin

to become the permanent capital of Texas. By the end of the 1850’s

the population had risen to a comfortable 3,494.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas Past"

August 1, 2013 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

|

References

for "The Capitals of Texas"

|

|

Davis, William

C., Lone Star Rising, (Simon and Schuster, 2004).

Fehrenbach,

T.R., Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans, (Da Capo

Press, 2000).

Grisham, Noel,

Crossroads at San Felipe, (Burnet, TX: Eakin Press, 1980).

Humphrey, David

C., Austin: An Illustrated History, (Northridge, CA: Windsor,

1985).

Humphrey,

David C., "AUSTIN, TX (TRAVIS COUNTY", Handbook of Texas Online

(http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hda03), accessed

April 2, 2013. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Jackson, Charles

Christopher, "SAN FELIPE DE AUSTIN, TX", Handbook of Texas Online

(http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hls10), accessed

April 8, 2013. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Johnson, John

G. "CAPITALS", Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/mzc01),

accessed April 8,2013. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

McComb, David

G., Houston, a History, (Austin, TX: University of Texas

Press, 1981).

McComb, David

G., "HOUSTON, TX", Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdh03),

accessed April 14, 2013. Published by the Texas State Historical

Association.

|

|

|