|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

|

Although

the Battle of San Jacinto lasted a mere eighteen minutes, it was

the culmination of six years of struggle. The struggle had its roots

in the oppressive Mexican Law of 1830 that banned American immigration,

in the disturbances at Anahuac

and Velasco,

in the arrest and imprisonment of Stephen

F. Austin, and in the

fighting that began at Gonzales and the siege

of San Antonio and led to the slaughter

of the defenders at the Alamo and Goliad.

On March 2, 1836, the convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos

declared Texas independence. Four days after the declaration, word

arrived from Colonel William Barrett Travis of the Alamo’s

plight. Unaware that the Alamo

had already fallen, Sam

Houston, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the Texas

army, immediately left the convention for Gonzales

to take command of the troops there and go to Travis’s aid.

Houston rode

into Gonzales

on March 11, and that evening heard from two Tejanos recently

arrived from San Antonio

that the Alamo had

fallen and that its gallant defenders had died fighting to the last

man. The tragic news was confirmed two days later by Susannah

Dickinson, wife of one of the defenders, who had been released

by General Santa Anna to spread fear and panic across Texas.

The dictator’s plan worked to perfection. Reports of the slaughter

at the Alamo terrified the people of Gonzales

and settlers throughout the area.

Panic stricken, the colonists believed Santa Anna would sweep eastward

with his well-trained army and kill every Texan in his path. Thus

began the frightened exodus known to Texas history as the “Runaway

Scrape.” The people hurriedly packed what possessions they could

carry in wagons, in carts, on horseback, and even on their backs,

and fled for their lives toward the safety of the Sabine

River and refuge in the United States. Knowing full well that

his few green troops were no match for Santa Anna’s veterans, Houston

evacuated Gonzales

and burned the town to the ground in the wake of his retreat.

|

|

|

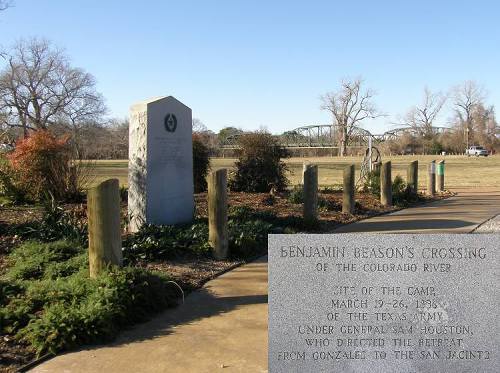

The

Texans crossed the Colorado River and marched 20 miles down the

east bank to Benjamin Beason’s crossing near present-day Columbus,

where they pitched camp on March 20. Had they been a few

miles further south, the troops may well have heard the distant

rumble of gunfire. On March 19,

Colonel James Walker Fannin was defeated at Coleto Creek by the

forces of General Jose Urrea. Fannin surrendered, and on Palm Sunday,

March 27, 352 Texans were marched out of the Presidio La Bahia at

Goliad and cruelly executed at the order of Santa Anna.

With the news of the massacre,

Houston’s men

rose as one and demanded an immediate attack on the Mexican army.

How else could they hope to avenge the loss of so many good friends

and family at the Alamo

and now Goliad?

Refusing to justify his decision, Houston

ignored their demands and ordered a withdrawal to the Brazos. On

March 28, the army arrived at San

Felipe de Austin on the west bank of the river, then crossed

over and marched to the plantation of Jared Groce where they set

up camp and drilled for two weeks.

Sam Houston’s

men were not alone when it came to urging him to fight. In mid-March,

the ad interim Texas government fled to Harrisburg from Washington-on-the-Brazos

when they learned of the Mexican army's approach. Interim President

David G. Burnet sent Houston

a letter demanding that he stop his retreat and fight. Burnet also

sent the Secretary of War, Thomas J. Rusk, to try and convince Houston

to take a more aggressive course. Houston,

however, much to the frustration of his army and the government,

also refused this request and stuck to his original plan, which

he continued to keep to himself.

Since Houston

appeared unwilling to put up a fight, Santa Anna decided to go after

the Texas government. After crossing the Brazos River at Fort Bend,

near present-day Richmond,

on April 11, he headed down the road for Harrisburg with

700 men, unwisely dividing the remainder of his forces so that he

might move more rapidly. General Urrea was at Matagorda

with 700 men, Colonel Gaona was between Bastrop

and San

Felipe with 725 men, Colonel Sesma had 100 men at Fort Bend,

and Colonel Filisola, with nearly 1800 men, was somewhere between

San

Felipe and Fort Bend.

When Santa Anna arrived at Harrisburg on April 15, he learned

that the Burnet government had fled down Buffalo Bayou to New Washington

(now Morgan’s

Point). Burning Harrisburg to the ground in anger and frustration,

the dictator hurriedly followed, but when he reached New Washington

on April 19, he discovered the government had once again fled, this

time toward Galveston.

Santa Anna then set out for Anahuac

by way of Lynchburg, but his advance elements got there just in

time to see the government officials sail away.

Meanwhile, Sam Houston

was determined he would not fight a battle until he reached ground

of his own choosing. He moved his army across the Brazos and headed

east, burning farms and crops as he went. There were few towns and

supply centers between San

Antonio and the eastern settlements, and when the Mexicans’

food and ammunition ran low, Houston

intended to make sure it would be impossible for them to secure

more. This strategy failed to satisfy the Texans, and they continued

to grumble their displeasure as the army marched eastward.

On April 17, the Texas army reached a settlement known as

“New Kentucky”

where two wagon trails crossed; one trail led to Harrisburg and

the other toward the Sabine

River. Most of Houston’s

officers and men had come to think of him as too timid to fight,

and they believed he would lead the army toward the Sabine,

where United States troops under the command of General Pendelton

Gaines waited to hopefully bail the Texans out if it became necessary.

However, much to the satisfaction of these non-believers, Houston

moved the column down the Harrisburg road.

From two prisoners captured by scout Deaf

Smith on April 18, Houston

learned that the Mexicans had burned Harrisburg and were following

the west bank of the San Jacinto River. He also heard that Santa

Anna himself commanded the column, and more importantly, that the

Mexicans had been forced by high water to cross the bridge over

Vince’s Bayou and would have to cross the same bridge on their return.

After considering the situation, Houston told the Texans they would

soon see action and to “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember

Goliad!"

|

|

|

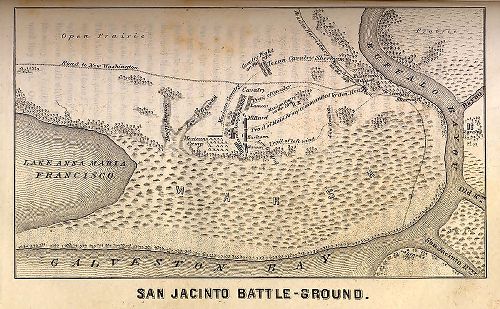

San Jacinto

Battle Ground Map

Wikimedia Commons

|

|

At

dawn on April 20, the Texans resumed their march, hoping

to arrive at Lynch’s Ferry before Santa Anna. Houston

sent an advance party to the ferry, and they found it guarded by

only a few Mexican soldiers. The Mexicans fled at the sight of the

Texans and left behind a flatboat loaded with provisions that were

most likely taken as plunder from Harrisburg. Capturing the provisions

was fortunate because the Texans had little supply of their own.

The Texans set up camp along a stretch of rising ground that ran

parallel to the bayou and was protected by a skirt of timber. The

“Twin Sisters”,

two cannons that were a gift from the citizens of Cincinnati, were

placed in the center under Colonel Neill. The first regiment of

riflemen commanded by Colonel Burleson camped on the right, and

the second regiment under Colonel Sherman set up on the left. The

cavalry was camped in the center at the rear of the infantry. The

Mexican camp stood less than a mile from the Texas camp. A marsh

spread out to the Mexicans' rear, and a temporary breastwork of

trunks, baggage, and other equipment protected their front.

That afternoon, a small detachment of cavalry commanded by Colonel

Sidney Sherman skirmished with some Mexican infantry. In the clash,

which almost brought the opponents to open battle, two Texans were

wounded, one severely and one mortally, and several horses were

killed. Mexican casualties were much heavier. Mirabeau Lamar, a

private from Georgia and later President of the Republic of Texas,

distinguished himself in the fighting and was placed in command

of the Texas cavalry on the eve of the battle.

|

|

Battle of San

Jacinto Painting 1895 by Henry Arthur McArdle

Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Wikimedia Commons

|

|

The

morning of Thursday, April 21, dawned bright and clear. Refreshed

from a good night’s rest and a breakfast of bread made with flour

captured from the Mexicans and meat from freshly slaughtered cattle,

the Texans were more than eager to launch an attack. They could

see the Mexican flags waving in the freshening morning breeze and

hear the mournful notes of the enemy’s bugle calls.

About 9 A.M., Deaf

Smith and his scouts discovered that, during the early morning,

General Cos had crossed Vince’s bridge with nearly 600 troops, increasing

Santa Anna’s strength to more than 1200. In response, Houston

ordered Smith

to destroy the bridge. The bridge’s destruction would not only prevent

Santa Anna from receiving further reinforcements, but also make

it impossible for either the Texans or the Mexicans to retreat toward

Harrisburg. Normally, Vince’s Bayou was about 50 feet wide and ten

feet deep, but heavy April rains had swollen it to a much more daunting

obstacle.

After his battle plan was approved by Secretary of War Rusk, Houston

formed the Texas army for battle around 3:30 in the afternoon. The

Texans’ movements were screened from the Mexican position by trees

and the rising ground that stretched between the positions. All

was quiet on the Mexican side during the afternoon siesta, and Santa

Anna had neglected to post any lookouts. The Texans formed their

line of battle with Burleson’s regiment in the center, Sherman’s

regiment on the left, the artillery, including the “Twin

Sisters,” under George Hockley on the right, and the infantry

under Henry Millard to the right of the artillery. The cavalry under

the command of Mirabeau Lamar formed on the extreme right.

At General Sam Houston’s

command, a battle line 910 strong advanced silently out of the woods

and swept up and over the long rise. Bearded, dirty, and ragged

the Texans may have been, but their long rifles were clean and well

oiled, and their features were set with grim determination. The

few musicians piped “Will you come to the Bower,” a popular love

ballad of the day, the men bending low as if preparing to face a

strong wind. As the troops advanced, Deaf

Smith galloped up and informed Houston

that Vince’s Bridge had been destroyed. The word spread quickly.

There would be no retreat. It was victory or death.

|

|

As

the range to the Mexican lines closed, the “Twin

Sisters” moved up and opened fire, sending a blistering load of

grapeshot boiling into the enemy barricade. With the roaring blast

of the cannons, the Texans surged forward as one man, screaming “Remember

the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” Blazing away with their

long rifles at nearly point blank range, they stormed over the makeshift

Mexican barricade, emptied their pistols, and then went at the Mexicans

hand-to-hand, using their rifles as clubs and slashing right and left

with their deadly long knives. The terrified Mexicans either fell

where they stood or ran in panic from the savage fury of the Texas

assault.

Hysterical pleas of “Me no Alamo!” and “Me no Goliad!”

echoed across the battlefield, but there would be no mercy tendered

this day. The enraged Texans quickly reloaded their long rifles and

went after the fleeing Mexicans, shooting, clubbing, or stabbing to

death any man they could catch. The terrorized Mexicans fled into

the boggy marshes at the rear of their position, but the bloodthirsty

Texans followed them even there, determined to kill every last man.

The water ran red with the blood of the slain. General

Houston, his ankle shattered by a Mexican musket ball, did his

best to call a halt to the senseless killing, but the fury of the

Texans knew no bounds and the massacre continued.

Sheer exhaustion finally brought an end to the slaughter, and Sam

Houston rode slowly from the field of victory. At the foot of

the oak tree where he had slept the previous night, the commander

of the Texas army slid off his horse and collapsed into the arms of

his chief of staff, Major Hockley. According to the official report

of the battle, 630 Mexican soldiers were killed, 208 wounded, and

730 taken prisoner. Balanced against this terrible toll, the Texans

suffered only nine killed, most of them in the initial Mexican volley,

and thirty wounded. In addition, the Texans captured a large supply

of weapons, ample stocks of supplies, and $12,000 in silver. |

|

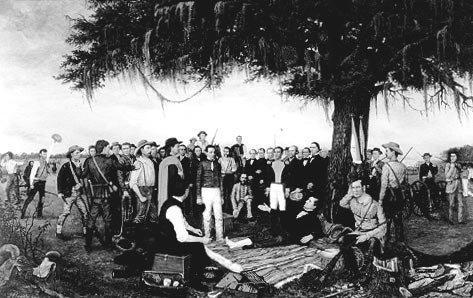

"Surrender

of Santa Anna” 1886 painting by William Huddle

Wikimedia

Commons |

|

Much

to Sam Houston’s

disgust, General Santa Anna had disappeared during the battle. The

following morning Houston

ordered a search of the surrounding area. That afternoon, Sergeant

J. A. Sylvester took note of a Mexican running toward Vince’s Bayou.

He caught the man hiding in some high grass. The prisoner was dressed

in a common soldier’s uniform, but when Sylvester took him to the

camp, the other prisoners recognized him and cried, “El Presidente!”

Santa Anna was brought to General

Houston, who was still lying under the same oak tree nursing

his wounded ankle. Houston

made it plain that he held no like for the dictator, and the Texas

soldiers crowded around him growling angry threats. Terrified, Santa

Anna whined, “You can afford to be generous, you have captured

the Napoleon of the West.” Houston retorted angrily, “What

claim have you to mercy, when you showed none at the Alamo or at

Goliad?” The two men sparred verbally for nearly two hours,

but in the end Santa Anna agreed to write an order commanding all

Mexican troops to evacuate Texas.

Later, Santa Anna signed the treaties

of Velasco, one open to public scrutiny and one executed in

secret, which recognized Texas independence. In eighteen glorious

minutes, Sam Houston

and his fellow Texans won a remarkable victory, establishing Texas

as an independent republic and opening the door for United States

expansion southwest to the Rio Grande and all the way west to the

Pacific Ocean. Few battles in history have been more decisive or

have had more far-reaching consequences than the Battle of San Jacinto.

© Jeffery

Robenalt April 1, 2012 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

References for "The

Battle of San Jacinto" >

More Battle of San

Jacinto - Related Articles

More "A Glimpse of Texas

Past"

|

Battle of San

Jacinto - Related Articles

The

Battle of San Jacinto April 21, 1836 by Murray Montgomery

Battle

of San Jacinto by Archie P. McDonald ("All Things Historical")

Lost

Letters from Travis' Saddlebags Spark Outrage by Mike Cox

San

Jacinto Day by Archie P. McDonald ("All Things Historical"

)

News of the fall of the Alamo on March 6, 1836, and the execution

of Texians captured at Goliad three weeks later, produced the terrible

Runaway Scrape, a mad flight of refugees who scrambled eastward

to escape a similar fate at the hand of General Antonio Lopez de

Santa Anna’s armies. In the midst of these troubles, one man, Sam

Houston, rode west...

Baker

Talk by Mike Cox ("Texas Tales")

"In modern times, battles begin with precision air strikes.

In the 19th century, battles began with stirring speeches. Sometime

in the early 1900s, the Beeville Picayune published the talk Captain

Mosley Baker supposedly gave to the men of his company at San Jacinto

on April 21, 1836..."

The

Top Ten Facts About The Construction of The San Jacinto Monument

San

Jacinto Monument by Mike Cox ("Texas Tales")

"Most people think the towering star-topped limestone monument,

built during the Texas Centennial in 1936, is the only San Jacinto

monument. Actually, it’s only the biggest."

Alfonso

(Alphonso) Steele - Last Texas survivor of the battle of San

Jacinto, and a State Park dedicated to him

The

Last Hero by Bob Bowman ("All Things Historical" )

The last surviving veteran of the Battle of San Jacinto on April

21, 1836, lies in an almost forgotten cemetery in deep East Texas

A

Frenchman at San Jacinto by Bob Bowman

Charles Cronea, a Jean Lafitte pirate who fought at the Battle of

San Jacinto.

The

Treaty of Velasco by Archie P. McDonald ("All Things Historical"

)

General Sam Houston, and later Interim President David G. Burnett,

chose negotiation instead of revenge for the massacres at the Alamo

and Goliad.

Twin

Sisters by Mike Cox ("Texas Tales")

The most famous pieces of artillery in Texas history

Smiths

at San Jacinto by Mike Cox ("Texas Tales")

Enoch K. Smith may have been the 17th Smith who took part in the

Battle of San Jacinto.

The

Mysterious Yellow Rose of Texas by Linda Kirkpatrick

A

Dalliance to Remember by Clay Coppedge

The

Yellow Rose of Texas by Barbara Duvall Wesolek

|

|

References

for "The Battle of San Jacinto"

|

|

Davis, William

C. (2004), Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas

Republic, Free Press, ISBN 0-684-86510-6.

Fehrenbach,

T.R. (2000), Lone Star: A History of Texas and Texans, Cambridge:

Da Capo Press, ISBN 306-80942-7.

Groneman, Bill

(1998), Battlefields of Texas, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas

Press, ISBN 97815566225110.

Hardin, Stephen

L. (1994), Texian Illiad - A Military History of the Texas Revolution,

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292730861.

Kemp, L.W.

"San Jacinto, Battle of," Handbook of Texas Online, (http//www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qes03),

January 8, 2012. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Maher, Ramona;

Gammell, Stephen; Rohr, John A. (1974), The Glory Horse: The

Battle of San Jacinto and Texas in 1836, Coward, McCann, & Geoghegan,

ISBN 9780698202945.

Moore, Stephen

L. (2004), Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the

Texas Independence Campaign, Rowan & Littlefield, ISBN 9781589070097.

Todish, Timothy

J. ; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998), Alamo Sourcebook, 1836:

A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution,

Austin, TX, Eakin Press, ISBN 9781571681522.

|

|

|